Seeds Of Resistance

“Atutwe no baana, tukale antomwe, tulye, tukanane.

As fire a gathering place to unfold.

The mortar and pestle, a vehicle and a motor

To tell the untold;

grain to grit and hand to heart.

Do you feel the rubble curdling and brewing underneath the cracking sheets of terracotta earth?

Mirroring the thunder threatening to rain without a drop

For we do not toil our communion to the earth, As Mama did,

Our harvest may be lost in between the ripe and ruin

The seeds that hold stories and song,culture and cries; left laying dormant, sleep (in)fertile soil.”

–Poem by Banji Chona

A vast majority of histories we know and have access to are products of colonial realities and stories.

These histories, predominantly penned by Western historians, have resulted in a skewed version of history and an asymmetrical archive. The asymmetrical mainstream archive sidelines alternative and often indigenous means of documenting and archiving histories. These alternative means of storytelling seldom have a direct link to the colonial frame of mind and elements, such as the English language or the canonisation of written history. Recognising alternative means of documenting and archiving history is an essential and critical element in writing or rewriting a crucial historiography of Zambia. This historiography includes the voices and experiences that colonialism has sidelined and repressed.

Within the context of Zambia’s indigenous, pre-colonial histories, seeds and plants function as living repositories, containing generations of historical narratives and stories. They are portals that can lead to a mapping of ancestral practices and an approach to understanding the past as a blueprint or guide in healing and addressing critical gaps in our stories as told through food sovereignty. Indigenous seeds and plants serve as more than sources of sustenance; they are a connection to the rich tapestry of ancestral knowledge and traditions. Each seed planted is a link to the past, carrying within it the wisdom and stories of generations past. By delving into the cultivation practices of our ancestors, we can uncover valuable insights into our heritage and identity.

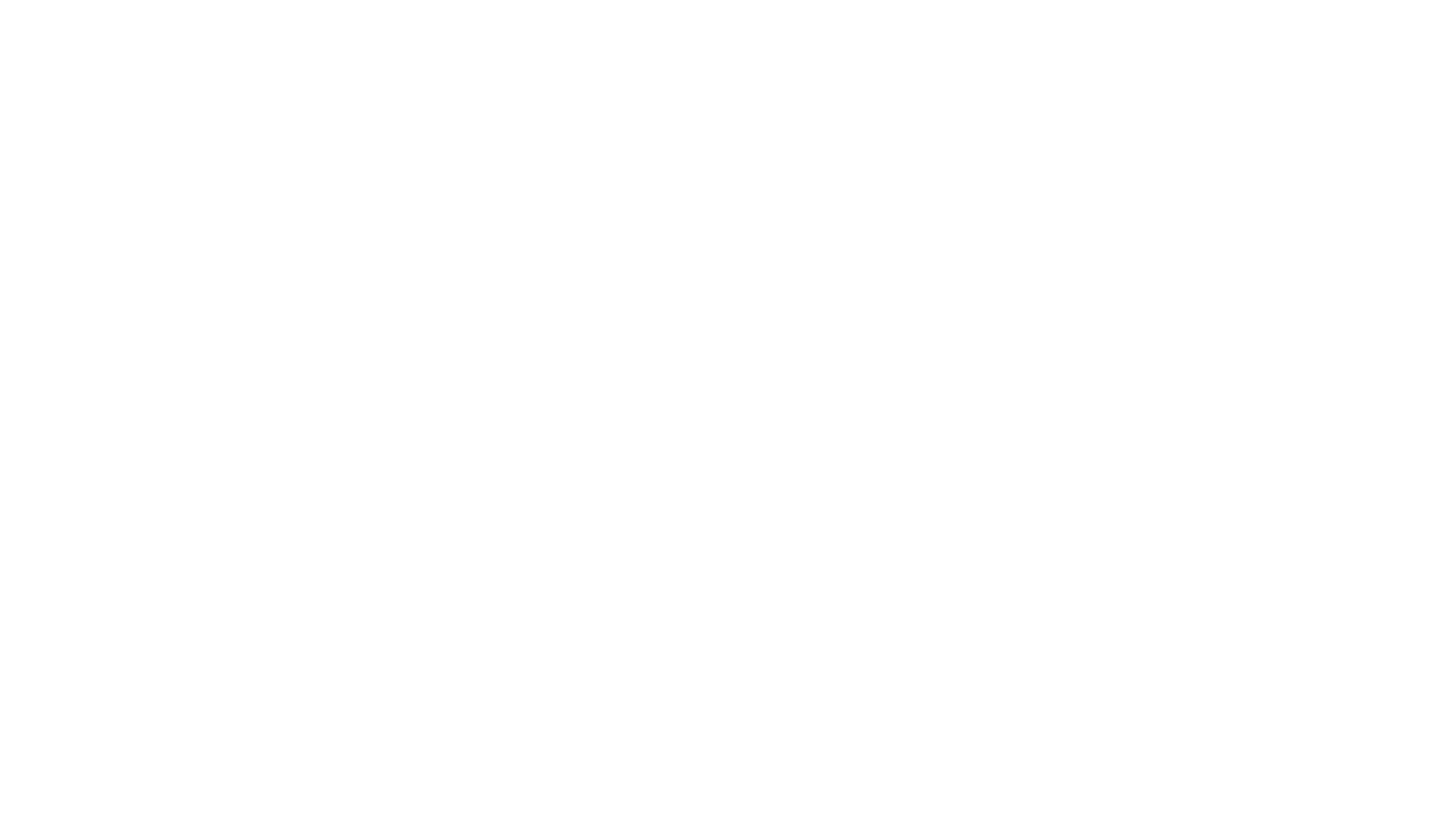

Women played a vital role in every step of the food production process, from the beginning − sowing the seed to the final preparation of meals. These tasks were not merely chores but integral parts of their lives, intricately woven into the fabric of their existence. The fields and gardens where the crops were grown, the forests where fruits were harvested, the open spaces in the village where grains were milled, and the thatched outside kitchens where meals were prepared became spaces where women’s voices could be heard, and their stories told.

The act of milling sorghum and millet was not merely a task of grinding grains but a communal experience rich in storytelling and cultural expression. Other indigenous foods that women processed included forageable foods such as mongongo nuts and musika (tamarind), which were used to add to various meals for added nutritional value.

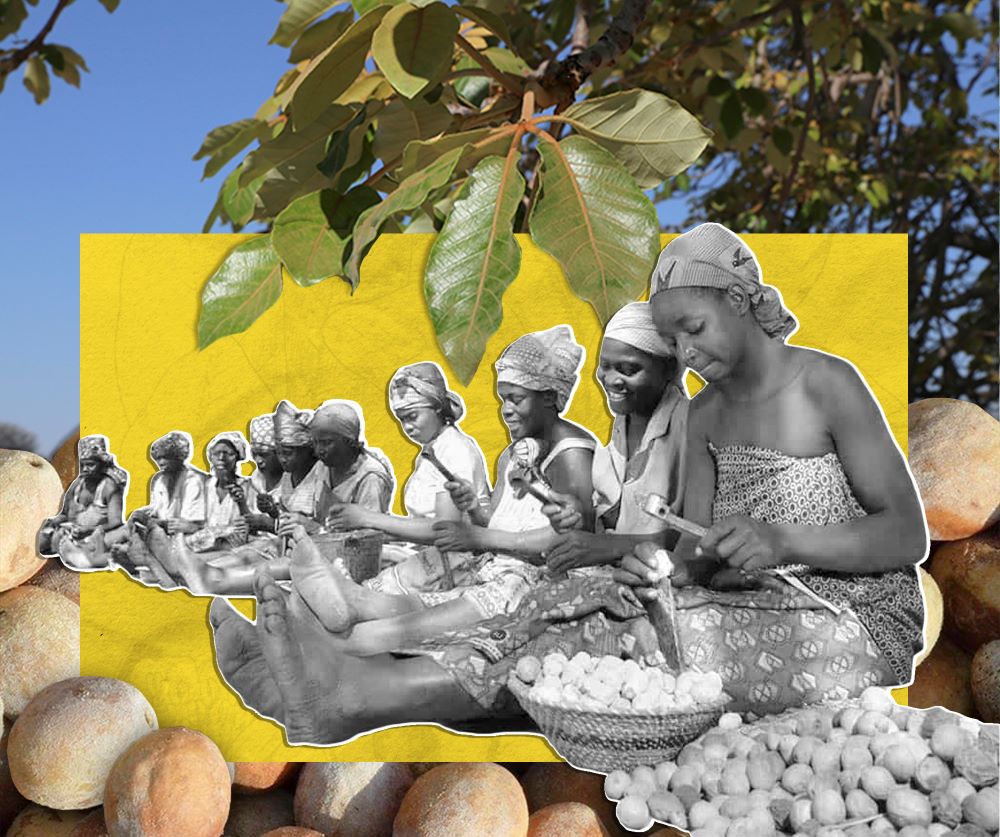

Women would come together in groups, forming a bond through shared labour in the central courtyards of their villages. As they rhythmically pounded the grains in mortars and pestles, they would weave stories and songs into the fabric of their work. Among baTonga women, this milling process Kutwa (ghoo-twa) was accompanied by traditional storytelling songs of the same name. Kutwa, which means “pounding,” offered a glimpse into the everyday lives of the women involved. Through the melodies and lyrics, they shared their joys, struggles, and relationships with their families and communities. The songs became a way to express emotions, narrate personal experiences, and connect more deeply.

The communal act of milling was not limited to food production; it was a celebration of community amongst women, resilience, and preserving culinary culture. These shared labour and storytelling moments created alternative spaces where women’s voices were uplifted, their stories honoured, and unique historiography unfolded. The sonic expression of personal and collective histories woven into food production processes led by women aren’t limited to baTonga across Zambia and Zimbabwe but are present across the Southern African region and the continent as a whole. The Chewa of Malawi have similar practices of work songs called machinga. Similarly, these incantations told the stories of women, who often had no space around conventional storytelling sites like fires.

“Apongozi

Iyayi

Apongozi

Zoona

Andilanda chimanga kumitondo

Nanga ine nditani njala yakula

Andilanda chimanga kumitondo

Nanga ine nditani njala yakula

Ali mbeta akwatiwe chaka chino kuli njala,

Ali mbeta akwatiwe

Chaka chino kuli njala”

This ciChewa pounding song tells the story of a daughter-in-law complaining to her mother-in-law about the theft of maize, which she was pounding the day before. The daughter-in-law also sings of being at a loss due to the famine in her village. Her advice is that those who are single should get married to avoid the famine that will hit the land that year.

Throughout time, these mediums of storytelling and archiving morphed in their shapes, sounds and processes. The changes resulted from many interventions impacting the trajectory of indigenous Zambian seeds. One particular plant eloquently tells the complex history of seeds and, thus, farming as we know it in Zambia today.

Maize.

Originally from the southwest highlands of Mexico, the seed arrived on the continent in the 17th century on the boats of Portuguese traders who intended for the seed to supply their trade posts. In time, through various iterations of systems of power and oppression, the seed was adopted by the indigenous people across the continent. In parts of West Africa, it is written that indigenous people were made to farm maize under duress by the colonial government and for white settlers; in exchange, they could ‘remain’ the custodians of their ancestral lands.

The homogenisation of the maize seed in Zambia can be traced to 1913 when the British colonial government Department of Agriculture introduced several test species of maize into their ‘experimental gardens’ in Chilanga and Mazabuka. These tests identified Hickory King as the most suitable variety of seed, and thus, it was made available for sale to white settler farmers. During the early 1920s, commercial farming of maize began to take root. White farmers began to adopt seed selection methods and to pay higher prices for better quality seed. By 1922, most white farmers were using their own selected seeds. Similarly, the Department of Agriculture began offering selected seeds to African farmers and encouraging their use. This period also saw the mechanisation of food processing, which indigenous farmers also adopted.

The introduction of chigayo (the hammer mill) dissolved and disintegrated the storytelling aspect within the culinary culture of kutwa. A single machine replaced the physical bodies and, thus, the voices of women who shared their projections of life and documented history through songs passed down through generations. Now, the chigayo stands alone, its mechanical whir drowning out the melodies of the past. The songs that once echoed through the village, carrying with them the essence of a people, have been silenced. The stories once woven into daily life’s fabric are now confined mainly to memories, fading with each passing season. Yet, amidst the clatter of metal and the machine’s hum, there is still a whisper of the old ways in which storytelling mechanics have morphed.

Despite ecological colonialism and its impact on indigenous culinary culture, the storytelling space still thrives where women gather around indigenous grains. In the marketplaces, behind stalls, women continue to care for and sell grains like maila, nzembwe; sorghum, and millet, which have persevered through changing times and soils in the spirit of resistance.

With their deep connection to the land and its bounty, these women carry on a tradition that is not just about sustenance but also about resilience and preservation of cultural heritage. As they meticulously sort through grains, their hands deftly working the familiar textures, they nourish bodies and keep alive stories of past generations. The marketplaces where these women congregate become more than just spaces to exchange goods; they are sanctuaries of knowledge and tradition.

Through their daily acts of tending to indigenous grains, these women preserve a way of life and reclaim a narrative once threatened by forces beyond their control. Each grain they lovingly handle is a testament to their strength and determination to keep their culinary traditions alive. In a constantly evolving world, these women stand as pillars of resilience, their actions speaking volumes about the power of community, heritage, and the unwavering bond between people and the land that sustains them.