Zambia at 60:

A Personal History

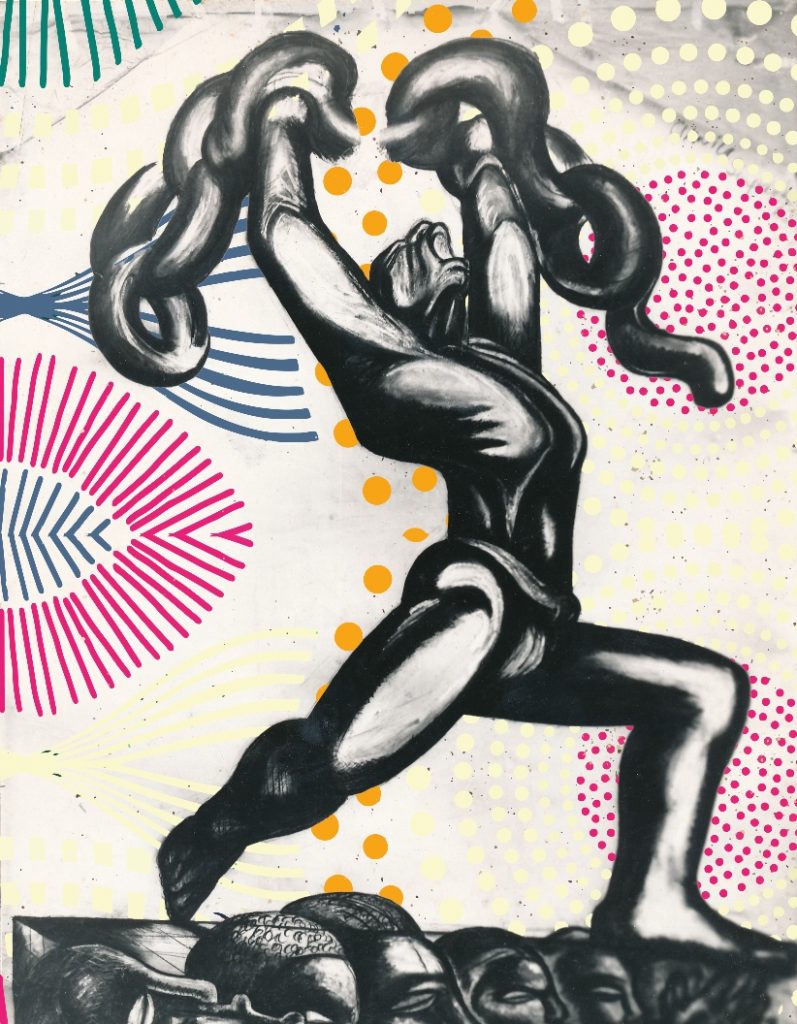

As Zambia marks 60 years of independence, the article captures the spirit of a nation built on sacrifice and hope, diving into the memories of those who experienced it. Personal histories intertwine to reflect the profound meaning of freedom, patriotism and unity of a nation destined for greatness.

They say youth is wasted on the young, and I say freedom is wasted on those who are born free. As Zambia celebrates 60 years of independence, I have never known what it is to live without freedom, which made me sceptical about writing this piece.

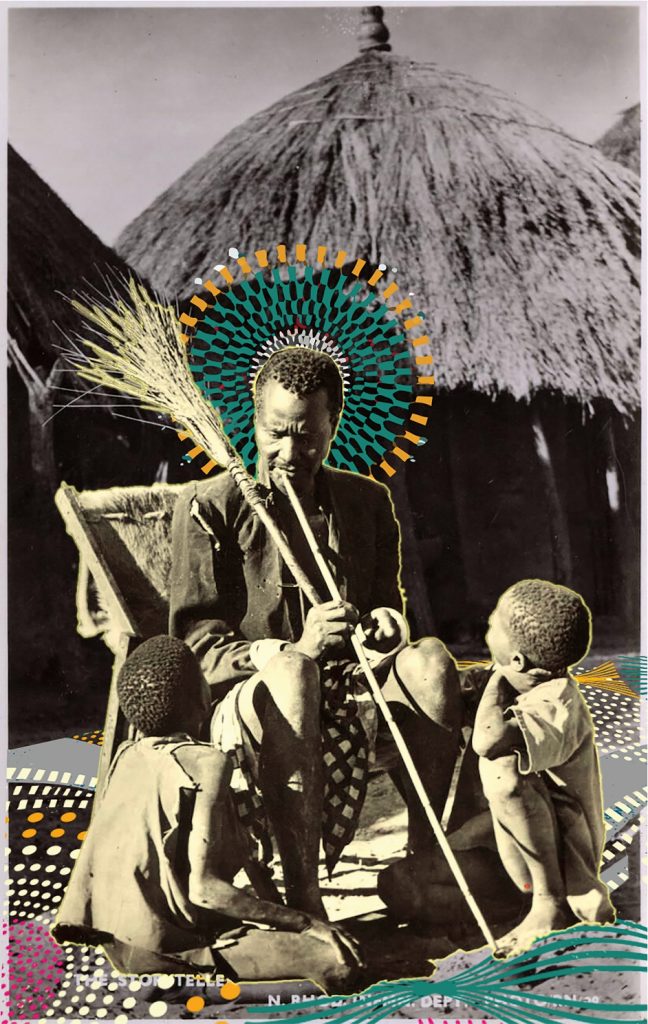

Growing up, my grandfather would tell and retell numerous stories from his youth, many of which are etched in my memory. He continues to regale listeners with stories from years past to this day. And I thought, what better way to reflect on this pivotal stage in Zambia’s history than by revisiting the storyteller’s life and career?

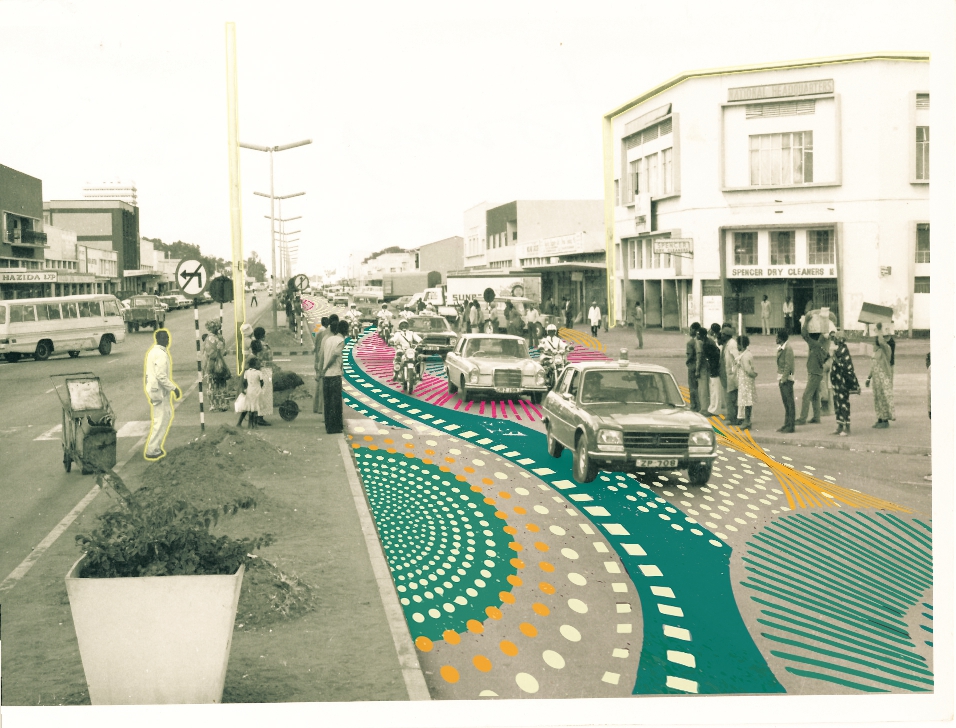

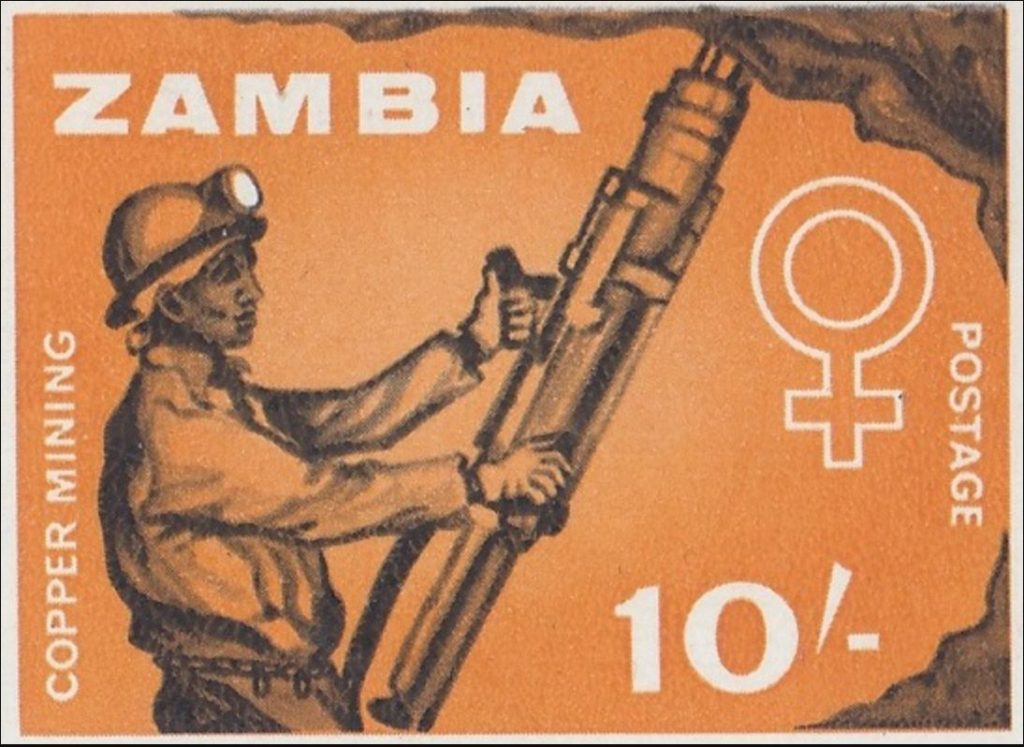

I was born in Lusaka during the waning years of the UNIP government. Zambia’s economy was struggling at the time. Copper exports, Zambia’s largest source of income, had decreased sharply, and basic goods were in short supply. My mother was also born in Lusaka, a month shy of Zambia’s second independence anniversary. At the time, the fledgling country’s economy was booming from the proceeds of copper, and it was a time of hope and anticipation for the future.

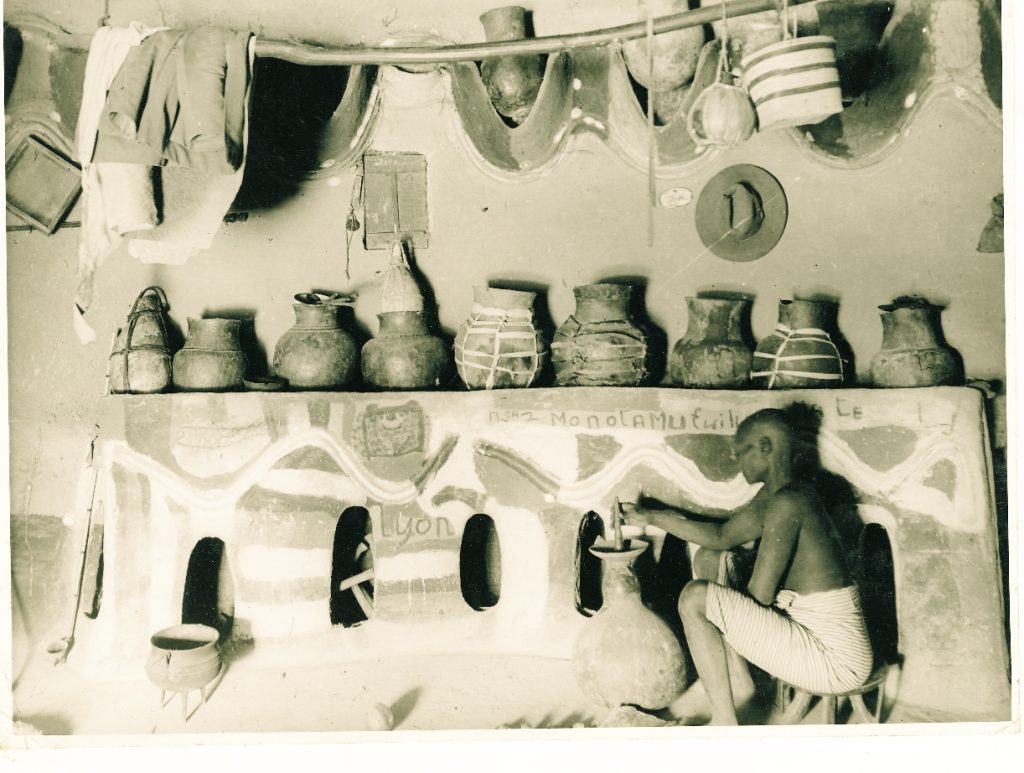

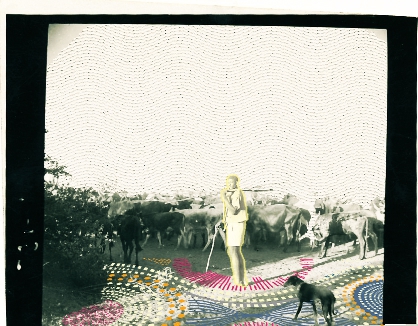

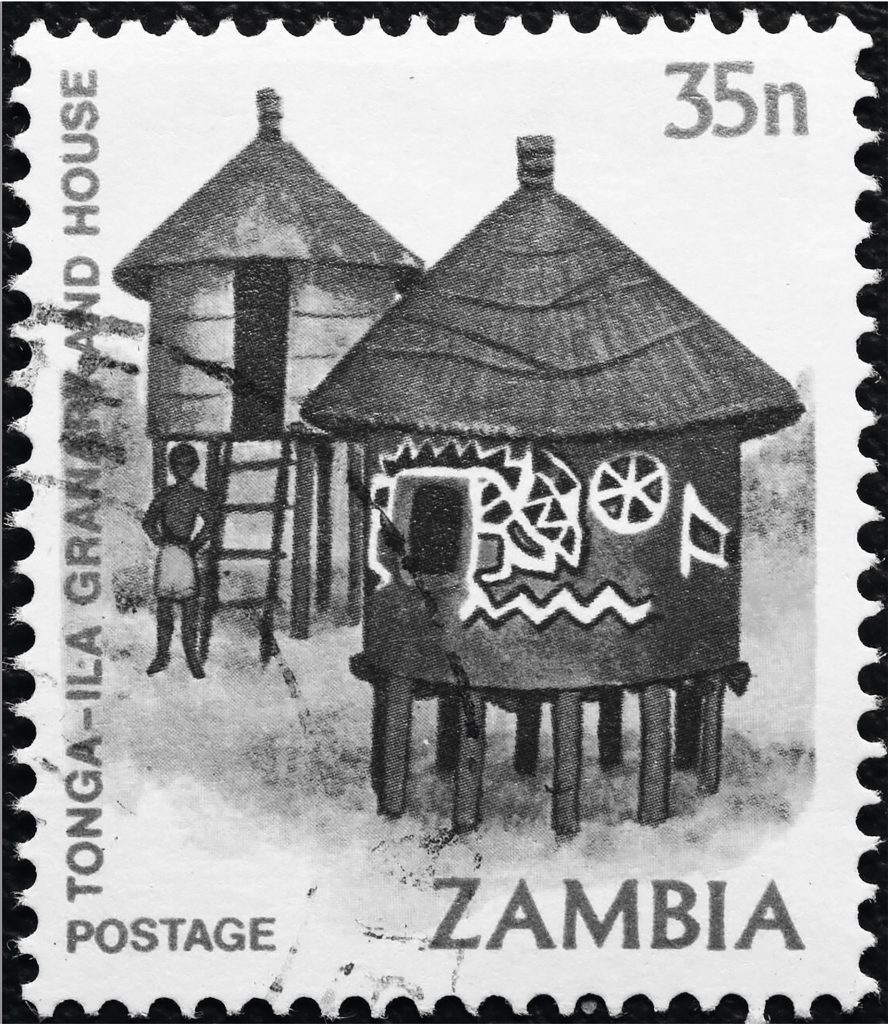

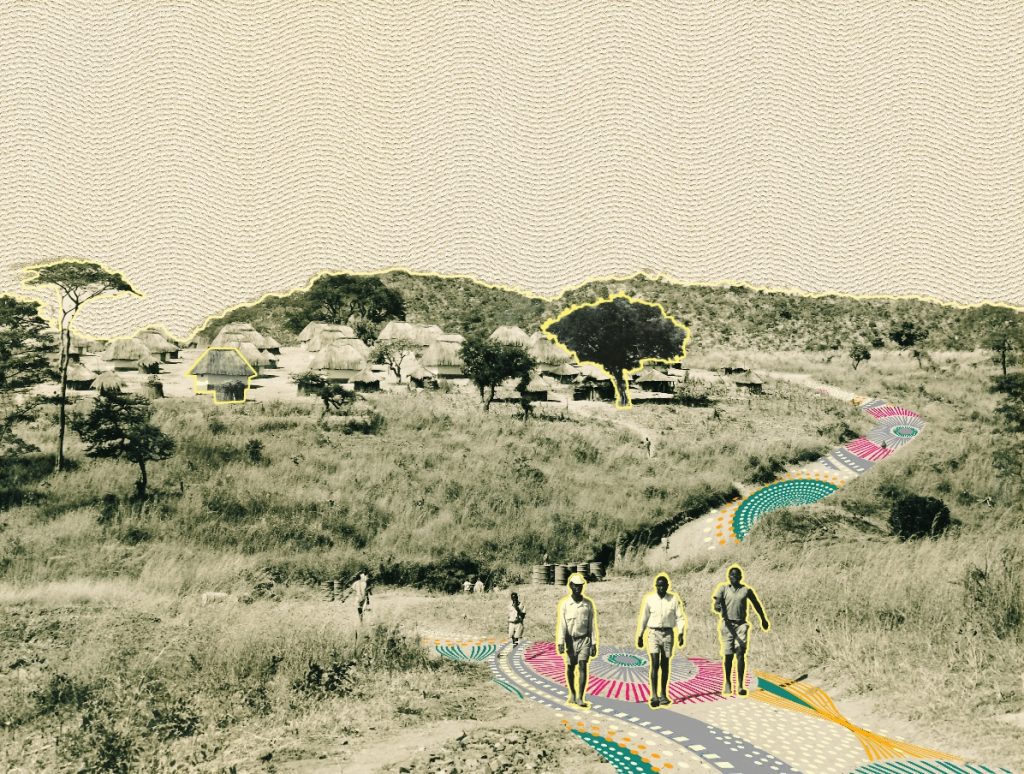

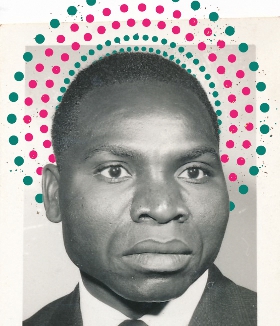

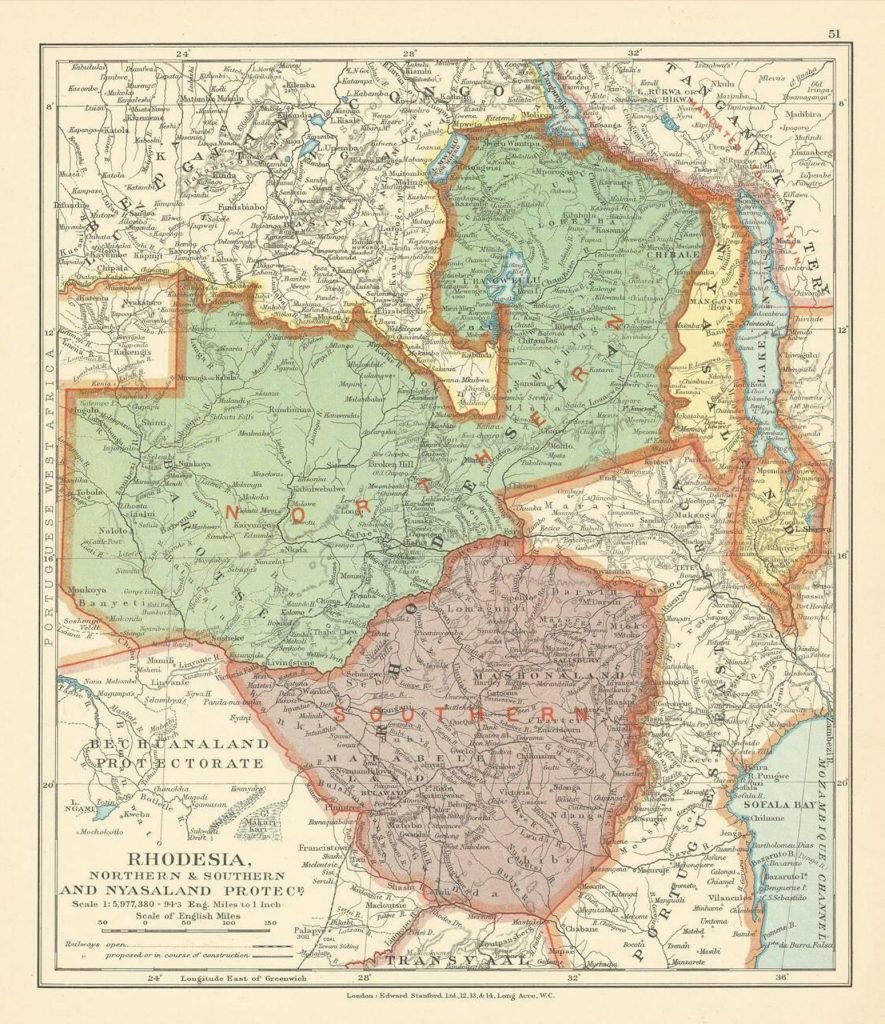

In contrast, my grandfather, Augustine Namakube Chimuka, was born in a completely different time and place to my mother and me. He was born in 1938 in Hamakulu Village in Chief Ufwenuka’s area in Monze District. Zambia did not exist then; it was Northern Rhodesia, a part of the British Empire. As he puts it, he was born into a typical Tonga village where life was simple and centred around culture. Cattle forms an integral part of Tonga culture, and adults and children alike participate in cattle rearing, with the village’s children regularly taking the cows out to graze and even daring to ride them for fun. A taste of fresh milk, or much preferred sour milk, was a reward for caring for the animals.

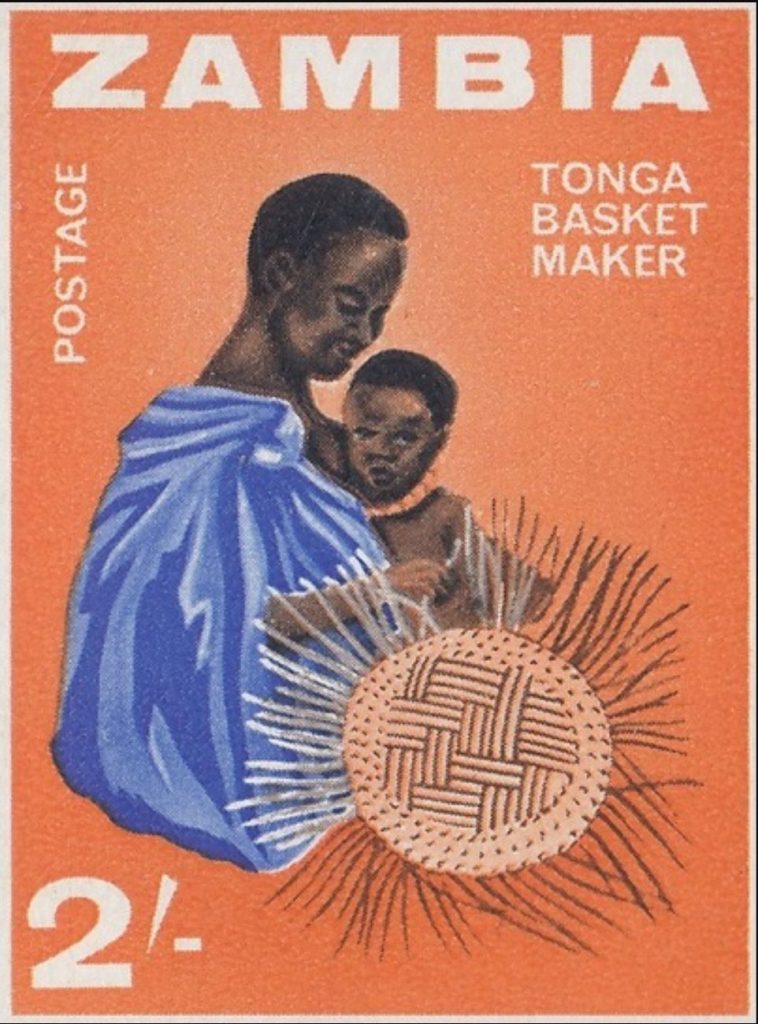

My grandfather’s mother, my great-grandmother, taught domestic science at the local school. She was known for her mastery of traditional Tonga basket-making and even more for her pottery.

My grandfather’s father, my great-grandfather, was the first person in his village to go to school. He was taught by Catholic missionaries and went on to become a teacher and officiant in the Church. He worked under the direction of the Reverend Father Joseph Moreau, a Jesuit priest who established the Chikuni Mission in 1905—the oldest Catholic mission in Zambia and what some refer to as the birthplace of Catholicism in Zambia.

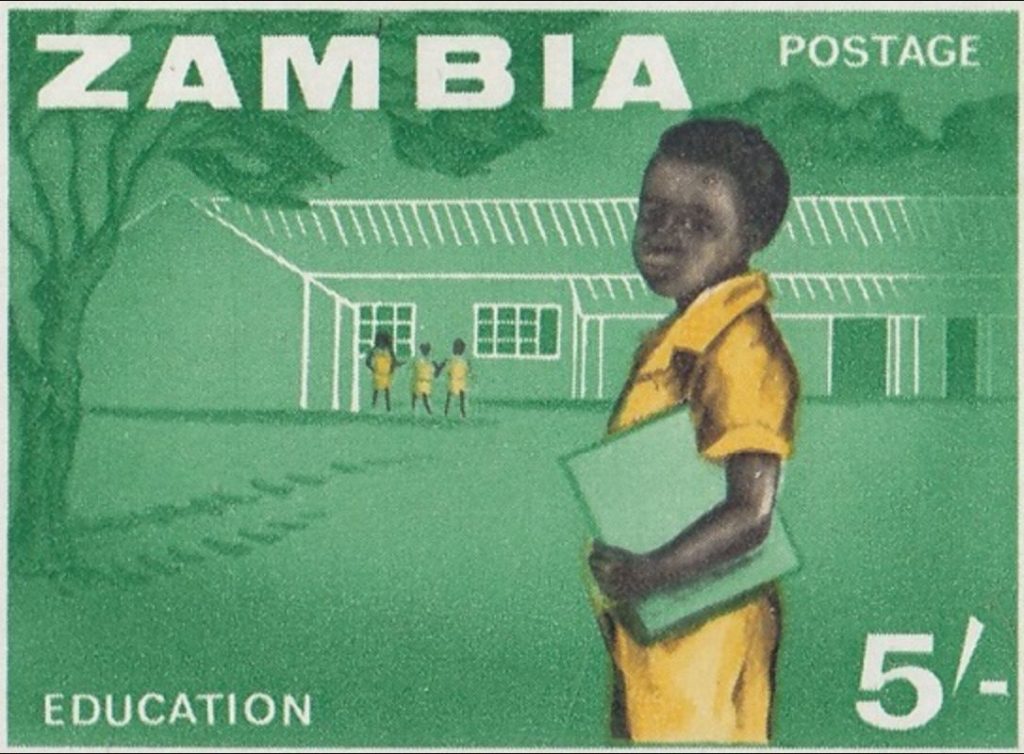

We consider education a right today, but in those days, it was something few privileged Africans under colonial rule could receive. After independence, the UNIP government ushered in free education for all, and it has been reinstated by the government of the day (up to the secondary school level). It was never a question of whether I would go to school but how many degrees I would earn.

My grandfather attended secondary school at St. Canisius College, located at Chikuni Mission. The privileged few who graced its halls came from across Northern Rhodesia to study there. For Form Six, my grandfather left the familiarity of the Jesuits for Munali Secondary School in Lusaka, the only school offering Form Six at the time. Established by the Rhodesian government, it was opened in the 1930s, making it the oldest secondary school in Zambia. Munali famously produced the vast majority of President Kenneth Kaunda’s first cabinet, with Kaunda himself being an alumnus of the school. Like Canisius, it served pupils from across Northern Rhodesia.

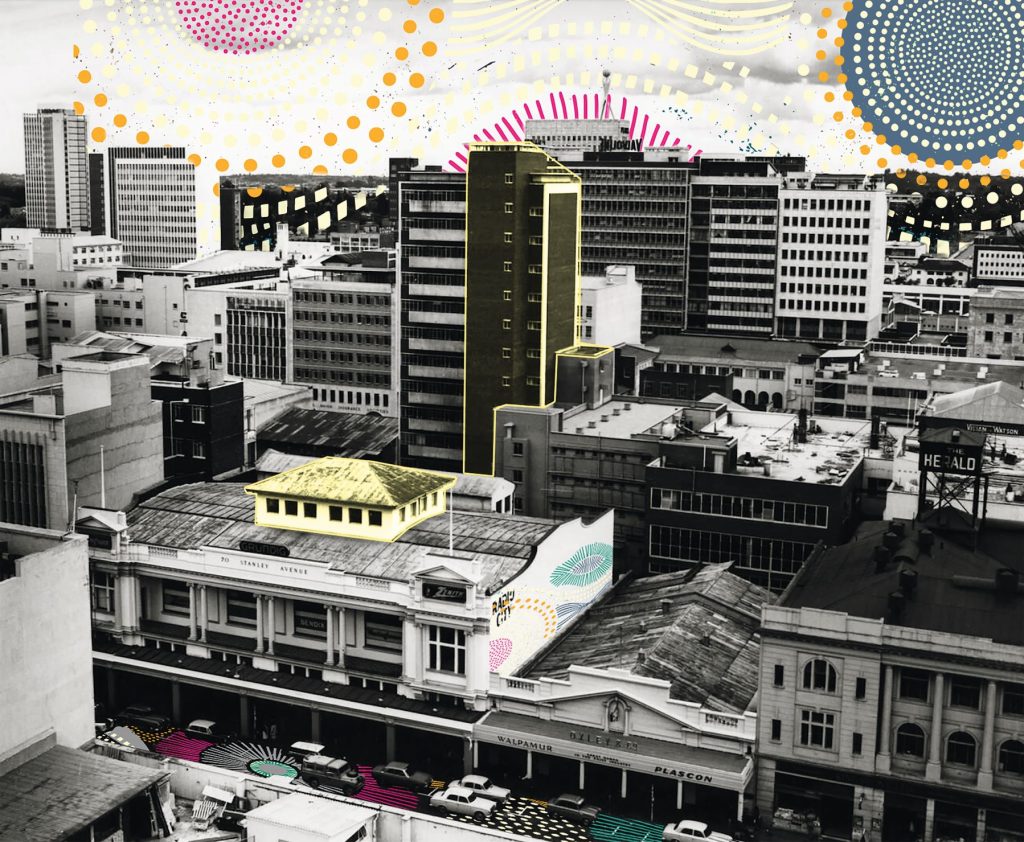

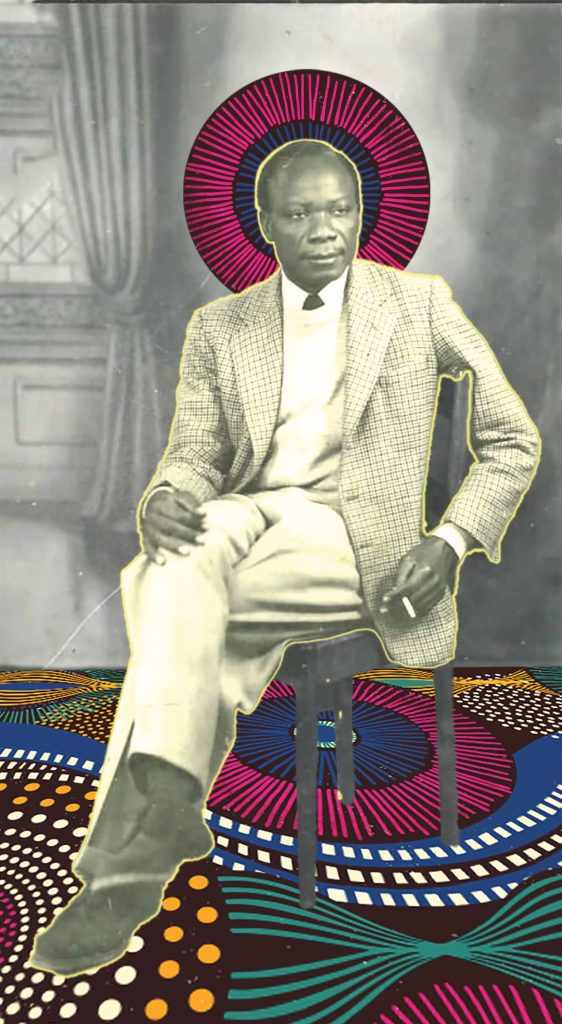

Continuing his education, my grandfather attended the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now the University of Zimbabwe) in Salisbury. This was the first racially integrated school he attended. He graduated in 1964, the year Northern Rhodesia became Zambia. Coincidentally, he was in Salisbury (Harare) on Independence Day. Spirits were high among him and his fellow Zambian students even if they couldn’t attend the celebrations in person. As he puts it, “There was a feeling of euphoria, even though we were in another country. Nyasaland (Malawi) had achieved its independence the year before, and we knew we were next.” He remarks that levels of patriotism were high and genuine. People were committed to serving Zambia and ensuring it was a success.

The new Zambian government had a monumental task ahead of it. To quote my grandfather, “They were essentially building a new nation from scratch and with almost no experience. However, they were committed, hardworking, full of integrity and were guided by a deep love for Zambia.”

By 1964, there were fewer than 100 university graduates in Zambia, and they were a precious commodity. Many entered the civil service, contributing to the government’s efforts to build a new nation. The University of Zambia (UNZA), the country’s first university, opened its doors to the public in 1966, intending to produce graduates who could develop the country. Today, Zambia is home to numerous public and private universities, something my grandfather finds heartening. He believes in the transformational power of education, which he describes as the great equaliser in society, especially for women and girls.

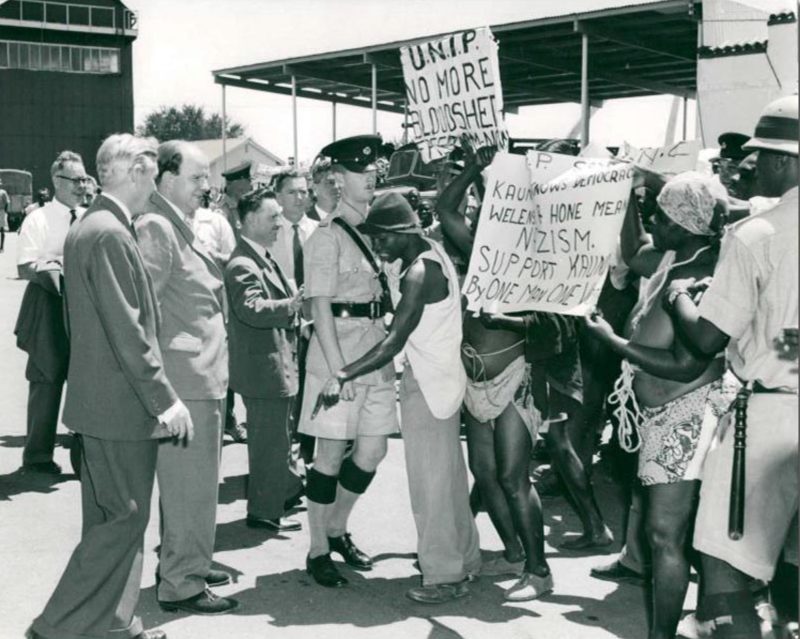

Despite his belief in the power of education, my grandfather had some misgivings, for while he furthered his education, he missed opportunities to participate in the independence struggle. As a pupil, he attended rallies and meetings for the African National Congress, established by Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula and some UNIP gatherings, though his participation was minimal. Having said this, he deliberately studied economics and political science at university with the goal of being an asset in an independent Zambia. Additionally, he strove to contribute to the independence of African countries still under colonial rule. To that end, while serving under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he worked at the Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union) at its headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

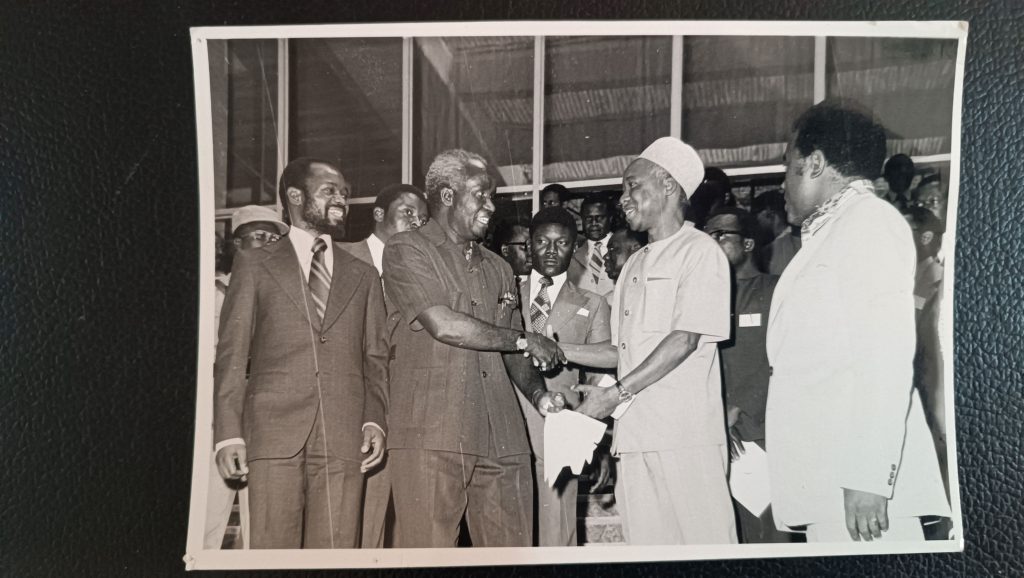

One of the main goals of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was the liberation of the entire African continent, and it was the right place to be if you wanted to support liberation struggles in Africa. Kenneth Kaunda, partly inspired by Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, was committed to contributing to the freedom of African countries and, along with Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, he was one of the leading figures at the OAU fighting for the cause of African liberation. Zambia hosted many exiled freedom fighters, including Thabo Mbeki, Oliver Tambo and Joshua Nkomo. Zambia paid a heavy price for this, including bombings by the Southern Rhodesian government led by Ian Smith.

Having served two terms at the OAU, my grandfather and grandmother, Masialeti Chimuka, née Mwikisa. My grandfather went on to serve in various ministries and at the State House, working under Kaunda and former President Frederick Chiluba following the return to multi-party democracy in 1991. This robust democracy has held firm to this day. He later retired and settled down on his farm on the outskirts of Lusaka, where he reared cattle just as he did as a young boy in the village.

I asked my grandfather what change struck him the most about post-independence Zambia. He sighed before responding, “The major change was seeing a fellow black person being head of state. The British governor was out, Dr Kaunda took the job…and we, Zambians, took over all the ministries.”

For 60 years, we have taken charge of our destiny, notwithstanding the impact of global political and economic factors. It is still hard to fathom that this was not always the case. Being a free Zambian is a privilege I often take for granted, but the paths and actions of my forebearers have contributed to my current reality in Zambia today. Whether they attended rallies or spearheaded independence movements, thanks to them, I’ve never had to experience colonial rule. We cannot truly appreciate what 60 years of freedom means without reflecting on life before freedom and the challenges faced once it was achieved.

Zambian history is our personal history, our lived experiences and the experiences of those who came before us. Beyond the facts and figures we can recite are real people, millions of unique lives woven into Zambia’s story. As we celebrate 60 years of independence and embrace the future, I encourage you to look back on your own family history and how it fits into the broader story of Zambia.

When I asked my grandfather what he wanted for Zambia in the next 60 years and beyond, he quoted the famous Kaunda slogan, “One Zambia, One Nation”. He says we must return to a spirit of unity and patriotism, like the early years following independence. He adds that, as Africans, we must work together as we did before to attain our collective freedom.

A newly independent Zambia, facing many challenges, prioritised nation-building, and, in a sense, we are still in the process of nation-building. Just as we overcame our challenges, we can triumph again, and Zambia can thrive in the next 60 years and beyond.