REVIVING ZAMROCK

There are no ceilings.

This was the first thing I noticed at Modzi Arts. In a world where we’ve been encouraged to shatter glass ceilings, what happens when there are no ceilings to shatter? This question lingered in my mind as Maingala Muvundika, the multi-talented accountant-photographer with the intriguing stage name, VFNGRZ (read Five Fingers; an ode to the two things that need five fingers in Zambia – deejaying and eating nshima), walked me through the doors.

People are places.

As we walked through the red doors that delineate the art space into areas, I grew convinced that if Mainga wasn’t a genius, this place had turned him into one. Modzi Arts was unlike any other art space I had encountered. It wasn’t just a gallery but a living, breathing entity. No wonder Zamrock, the iconic Zambian rock genre, had found a home here. Modzi Arts exudes a vibrant, incomplete charm, reflecting the essence of something alive and evolving. As a visitor, I, too, felt a sense of belonging in this dynamic space.

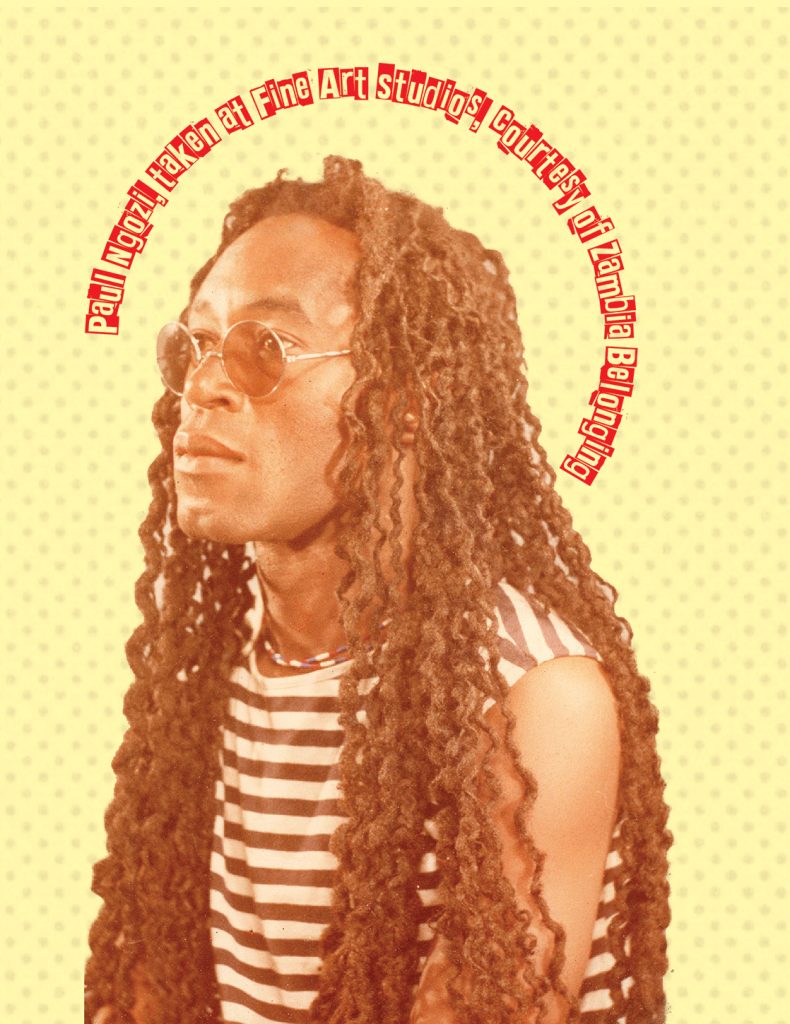

As my guide for the day, Mainga led me to a Zamrock Living Exhibition that sounded exactly like it was – a living room. In the room, Zamrock springs to life through guitars, a hat only a rockstar would wear, iconic picture prints of the legendary Paul Ngozi, stacks of books about Zamrock and a turn-table ready to placate listeners with the latest offering from the excellent Witch band. I almost didn’t want to touch it, but I did. It is the place I will remember as my official encounter with Zamrock.

“By the mid-1970s, the Southern African nation known as the Republic of Zambia had fallen on hard times….”

“This is the environment in which the ’70s rock revolution that has come to be known as Zamrock flourished in Zambia’s capital of Lusaka and the copper-rich “Copperbelt” province cities of Zambia’s north, specifically Ndola and Kitwe.” – excerpt from Welcome to Zamrock! Vol. 1.

I’ve heard of Zamrock as an abstract idea attached to sounds, sacred to the people before me, but I never wrapped my head around the need for the resurgence of a lost genre. In the world of museums, we often associate the term with physical spaces, carefully curated artefacts and historical collections. However, if we look beyond the conventional definition, can a person also be a museum, an institution, or a vessel of knowledge?

As we traditionally understand them, museums serve as repositories of knowledge, housing relics and objects that offer glimpses into the past. Yet, the term “museum” can be problematic for many Africans and many who associate the term with displaying and curating artefacts that are not always framed in the correct context by the right people.

Enter the Zamrock Museum, a unique entity challenging the conventional notion of a museum. While boldly challenging the Western definition of a museum, it also does something extraordinary: transforming individuals into living institutions of knowledge.

Experimental by nature, Modzi Arts is an evolving art space. At the front of the yard is a clay structure under construction with an intricate clay wall pattern. The Museum is a brainchild of Julia – Ba Taonga, the director of Modzi who was inspired by traditional Lenje architecture and infused part of her cultural identity into the construction. Once complete, the sphere will be christened The Zamrock Museum. The women pensively mould the clay walls and the floor. At the same time, the men thatch the roof, ultimately creating a sustainable, environmentally friendly structure that will grow stronger the longer it stands. It is a physical place to honour the musical relics, the stories and knowledge of Zamrock.

What is Zamrock, and why does it matter?

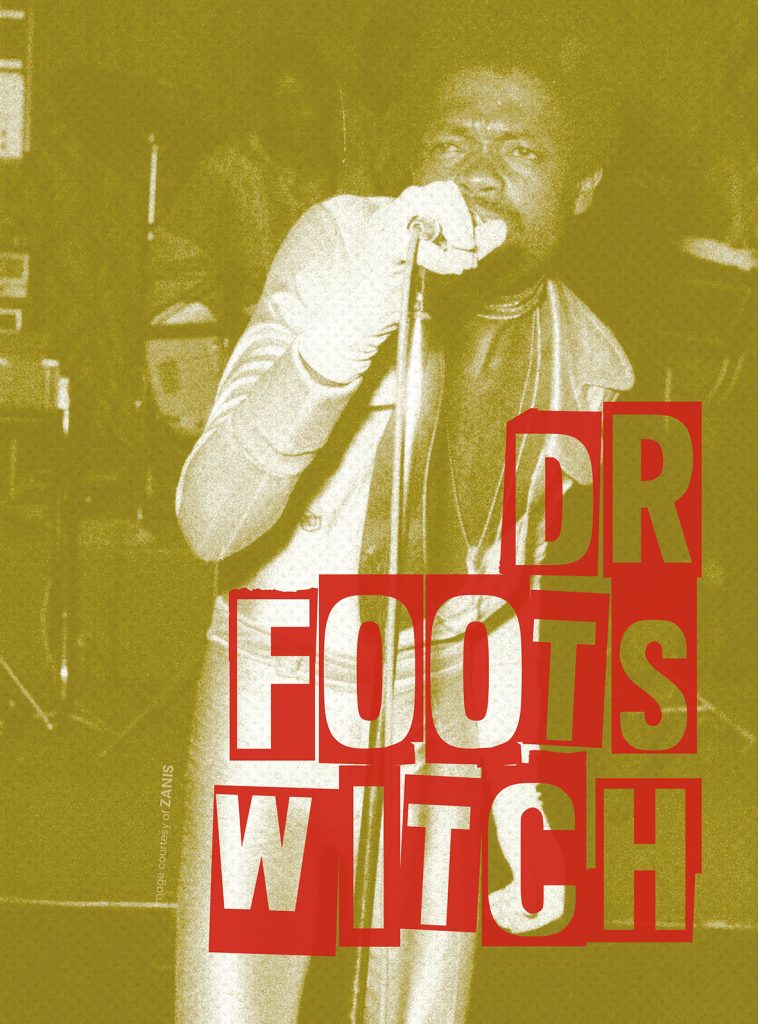

Zamrock emerged in the 70s on the coattails of the sounds of the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and James Brown. Zambian musicians experimented with the sounds, lyrics and feel of hits on global top charts until their experimentations evolved into a genre, a body of work with a guide for instrumentals, sound progressions and a space for social commentary. The result was an emergence of Zambian bands from every region.

Music is alive. We hear of the greats like the Ngozi Family, Mosi-O-Tunya, Witch, Blackfoot and Salty Dog, but there were many more. Keith Hamusute nods to this era of Zambian music in his novel The Ghosts Came To Dinner and Never Left. Today, Travis Scott has sampled Keith Kabwe on his Utopia album; Sampa The Great proudly heralds this genre and has received recognition globally and locally. In their respective manner, these individuals form part of the Zamrock living museum.

The Zamrock Museum expands far beyond the confines of four walls and a roof. It is not simply a ‘place’ in the way we define ‘place’, but rather a dynamic force fostering residencies, collaboration, and education. At the heart of the Zamrock Museum’s mission is the perpetuation and propagation of Zamrock’s rich heritage. Modzi Arts has trained 79 people as part of the Zamrock Museum to showcase the work of their alumni and pass on this knowledge. This extends beyond musicians; it encompasses artists, DJs, curators, booking agents, artist managers, and anyone passionate about preserving and sharing this cultural treasure. The knowledge of Zamrock is not stored in static exhibits but is actively embedded into individuals who become living embodiments of this legacy.

The music and gallery streams are focused on Zamrock and have birthed the seven exhibitions that incorporate sound, light and storytelling into the archiving of this essential part of Zambian history. The exhibition has seen evocative installations from artists such as Banji Chona and archivists like Sana Ginwalla and bridged the gap in space and time to bring people closer to the disruption of the Zamrock era.

What killed Zamrock, and does it deserve to live?

The short answer is time. The passing of time brought Zamrock to its end, and the passing of time is why we must remember it and keep it alive. Within time’s canon, we see things like the socio-economic impact of the HIV/AIDS pandemic on musicians, the friction of changing human interest, religion, and morality, and the constant pursuit of better opportunities.

Time is change, and change alters us. But we are here, a culmination of everything we are and all that has happened to us.

When you interact with an alumnus of the Zamrock Museum’s residencies, you are, in essence, engaging with the “museum” itself. Each conversation and each dance floor experience becomes an exhibition of Zamrock’s vitality and relevance. This transformation makes Zamrock more than a relic of the past; it is a living, breathing entity that continues to inspire and educate future generations.

In redefining the concept of a museum through the Zamrock Museum’s model, we discover that knowledge, culture, and heritage are not confined to static displays. They are dynamic, ever-evolving forces that can be carried within individuals and shared with the world. The Zamrock Museum is a testament to the enduring power of culture, and it challenges us to reimagine the role of museums in preserving and perpetuating our shared human heritage.

In the music, you taste the history of Zambia and catch a glimpse of a past that is still so real through our living museums like Jagari Chanda and Rikki Ililonga. They embody the memories of our rising; through them, we can understand what Zamrock means and allow it to merge with our identity and pass it on.

The greats are full of lessons about business, identity and the art of music production. Modzi has residency programmes that condense these lessons on proper archiving, music recording, and ownership to bring the new crop of Zambian musicians closer to lucrative careers that birth legacies. Perhaps Zamrock must live so we can soar on the wings of the greats. Though it is old, it is not forgotten. By reading this, you and I have become co-conspirators in keeping a musical piece of our history alive.

If a thousand words are too long for you to read, visit Modzi Arts and experience Zamrock because it is happening there.