Reclaiming Indigenous Foodways:

Ancestral Practices for Drought Resilience

Loongo stood in the doorway of her mother’s thatched hut, her petite frame and clay-coiled curls silhouetted against the deep blue sky. She squinted, shielding her eyes from the merciless sun. The nimbus clouds she hoped for were nowhere in sight. It was December, three months into the rainy season, yet not a drop of rain had fallen. The earth was a cracked mosaic of despair, with even the most resilient seeds, like sorghum and millet, lying dormant or struggling to sprout in Nampeyo’s unforgiving heat. The cows were thin, leaning their waning bodies against the trunks of mubuyu, the baobab.

Her gaze shifted to her mother, Luba, who sat in the shade of a large musikili tree, the rumble of incelwa, her pipe, a comforting sound. With its sprawling branches and thick foliage, the tree was a rare respite in the arid landscape. Luba’s voice carried softly through the still air as she sang an old song, her words weaving hope and weariness. It was a song passed down through generations, telling the story of her people in Munyumbwe, a village in the Valley.

“In 1910,” Luba sang, her voice steady and fatigued, “the drought came upon us, fierce and unyielding. The rivers ran dry, and the crops withered. But our ancestors, strong and resourceful, scoured the grasslands. They gathered the bones of animals long gone, pounded them into powder, and made a soup that sustained them through the harshest times.”

Loongo listened intently, puzzled yet captivated by the tale. Surviving on a soup made from animal bones seemed mythical to her, a story from a different time. Yet, the strangeness of it gave her hope. If her ancestors could find such a solution in dire adversity, perhaps there was hope for them, too.

Luba’s song continued, painting pictures of perseverance and unity. “Together, they shared their meagre soup, each spoonful reaffirming their strength and solidarity. They sang songs of hope and danced around the fires, their spirits unbroken by the drought. And when the rains finally came, they rejoiced, knowing their courage and belief in mizimu, the spirits, had seen them through the darkest days.”

As Luba’s song ended, she looked at Loongo and smiled, a weary yet reassuring smile that spoke of love and faith. The pipe’s rumble returned. Loongo felt a surge of determination. She would be brave like her ancestors and find a way to endure.

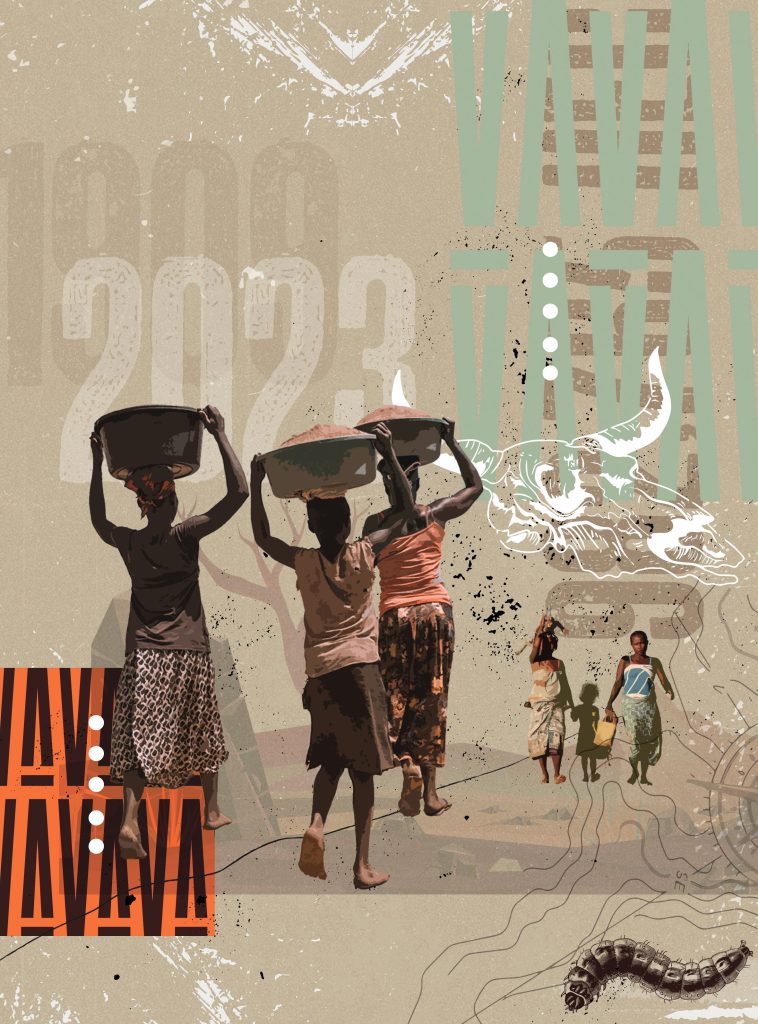

Zambia has a widely documented history of drought-related famine and food insecurity over the last century. The seasons of dry spells and scorching temperatures can be attributed to climatic factors such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation. During El Niño events, which occur on average every three to five years, the interior landmass of the southern part of the continent often experiences reduced rainfall, leading to drought conditions like those recorded in 2023-2024.

In the 20th century, the droughts experienced across the region were recorded in the oral histories of Zambian tribes. baTonga oral history marks the calendar years of drought as starvation years. The starvation years were given names reflecting the collective experiences of the people. The period between 1909 and 1910 is known by the Valley Tonga as Nzala Ya Panaamafuwa, the starvation year of eating the bones. People searched the Valley for mafuwa, bones, which were pounded and eaten. 1987, an El Niño year, is known as Nzala ya Kubula Kwamvula, the starvation year of no rain. During this period, the people of the Valley survived on forage foods such as edible caterpillars and fruit from the baobab.

The Role of Indigenous Knowledge

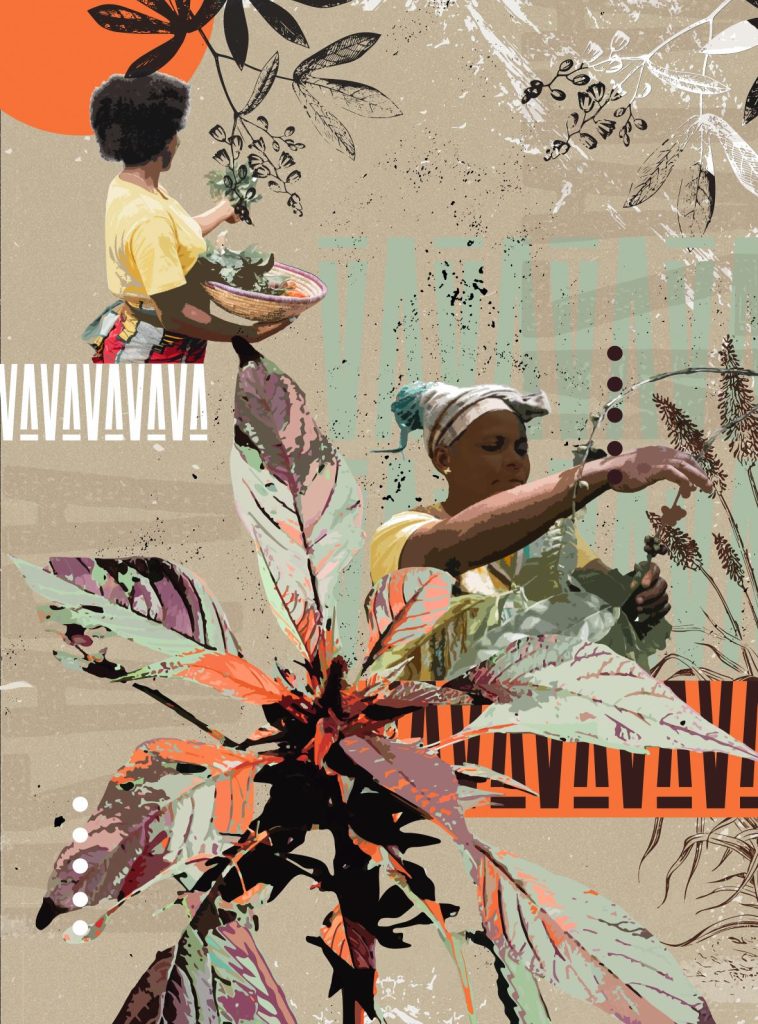

During times of drought and food insecurity, in places like Nampeyo, the deep knowledge of forage plants embedded within the systems of baTonga enabled them to surpass the conditions through the consumption of wild fruit, tubers, and grasses. The foraging practices of baTonga are part of a generational system of living from the land and play an integral role in sustaining the community’s diets and nutritional needs. Women and girls would gather in groups and walk up to 30 kilometres into the surrounding Southern Miombo Forest to forage and dig for lusala (Dioscorea hirtiflora bent). This indigenous tuberous climbing plant grows wild yams beneath the soils. In drought times, when other foods were scarce, lusala was peeled and boiled; during times of abundance, it was blended into various meals such as fish and vegetables or made into buntele, a groundnut powder dish. As both a staple wild food and a famine food, lusala has remained a plant that continues to sustain the nutritional needs of communities in the Southern Province. Other forage foods such as the marula fruit (Sclerocarya birrea) and bondwe (Amaranthus spp.), an annual species of wild leafy vegetable, have remained embedded within the diets of baTonga and become staples in many Zambian cultures.

Modern Drought and Solutions

In the current drought ravaging Zambia and parts of the Southern African region since the third quarter of 2023, a return to these knowledge systems and practices could serve as one of the responsive approaches to the food security crisis. The 2023/2024 drought has been recorded as the driest agricultural season in the last sixty years. The sharp decline in rainfall and rise in global temperatures has caused harsh climatic conditions, leading to catastrophic effects for humans and the natural world alike. Towns like Monze and Mazabuka, known for their verdant landscapes, now stand desolate and arid. Fields that once provided for communities and their kin are either bare or dotted with wisps of fragile stalks being motioned by the winds.

Since October 2023, a total of 982,765 hectares out of an estimated 2,272,931 hectares of maize sown across the country have dried up and curled at the root. The total failure of the maize seed and crop has led to increased food insecurity across numerous households reliant on agriculture, either as a source of income or nutrition. A report by the United Nations approximated that 2.04 million people at the end of the lean season, October to March, were severely food insecure and in need of humanitarian aid.

Embracing Ancestral Practices

Returning to naturally occurring and acclimated ancestral food sources, both cultivated and foraged could address the environmental and socio-cultural gaps presented by the drought. Historically, foraging and cultivating soil and plants in both dry and abundant seasons were the roles of women and children. Through their knowledge of the land, they saved their communities from starvation. This knowledge could be unearthed and shared across various provinces and passed down through generations, reclaiming ancestral practices to solve contemporary challenges. By tapping into these traditional practices, communities can build resilience against future droughts and environmental challenges.

Emphasising sustainable agriculture and foraging can reduce dependency on external food aid and promote self-sufficiency. For instance, cultivating drought-resistant crops like sorghum and millet can provide a stable food source even in harsh conditions. Additionally, educating the younger generation about these practices ensures the preservation and continuity of vital knowledge.

Government and non-governmental organisations can play a crucial role in facilitating this revival. Initiatives such as community workshops, school programs, and local farming cooperatives can provide platforms for sharing and practising ancestral agricultural techniques. These efforts could also include creating seed banks of indigenous plants, ensuring that future generations have access to these critical resources. Furthermore, integrating modern technology with traditional knowledge can enhance efficiency and yield. For example, using weather prediction tools can help farmers plan their activities better, while sustainable irrigation techniques can improve water use in agriculture. Combining the wisdom of the past with the tools of the present can create a robust agricultural system capable of withstanding environmental stresses.

Pathway to Resilience

Embracing and revitalising ancestral food practices offers a pathway to address current and future challenges. By doing so, communities honour their heritage and create a sustainable and resilient food system. This holistic approach can lead to improved food security, environmental stewardship, and socio-cultural cohesion, ensuring a better future for generations to come.