Goodbye, Robben:

Triumph of Robben Island

“While we will not forget the brutality of apartheid, we will not want Robben Island to be a monument to our hardship and suffering. We would want it to be a triumph of the human spirit against the forces of evil. A triumph of wisdom and largeness of spirit against small minds and pettiness; a triumph of courage and determination over human frailty and weakness; a triumph of the new South Africa over the old.”

— Prisoner No. 468/64, Ahmed Kathrada

A trip to Cape Town is always cause for celebration in my books. Beautiful beaches, a plethora of cuisines to choose from, mouth-watering wines, the list is endless. The Mother City (as Cape Town has been affectionately christened) lives up to its name in many respects, offering coveted respite to holidaymakers and luring both locals and visitors into various pockets of the city. I suppose one cannot separate the word holiday from Cape Town — they are firm synonyms. Yet, for all its beauty, the Mother City is a conduit of history that is a sobering reminder that Cape Town was once the crowning glory of a colonial, and later apartheid, state.

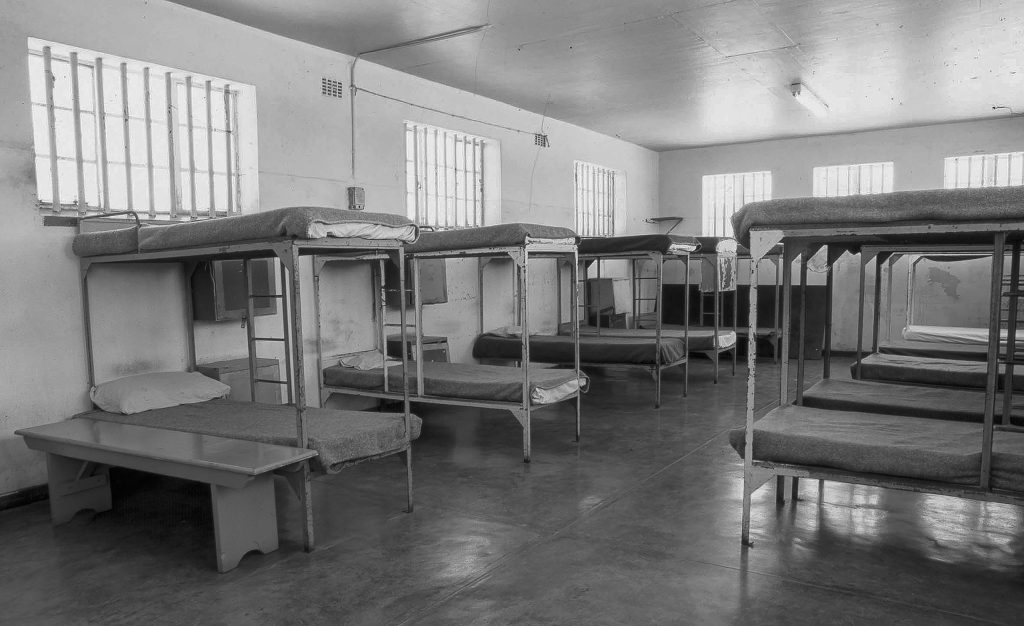

The apartheid prison, which operated from 1962 to 1992, was a maximum security prison built by black prisoners under harsh working conditions. It was built to hold the fiercest opponents of apartheid.

I decided to visit Robben Island on one of my excursions into the city, partly because I had been robbed of the opportunity on my first-ever trip to Cape Town (a long story for another article), and mainly because I wanted to see the place that has become a symbol of tenacity for South Africans and many people across the world. Robben Island is a small island located off the west coast of Bloubergstrand, a suburb in the northern part of Cape Town. Following Bartholomew Dias’ arrival on the island at the tail end of the 15th century, Robben Island began as a refuelling station for ships in transit to India. The island functioned as everything from a quarantine station to a military base in the centuries to come. In the 20th century, the apartheid government began using the island as a prison for political prisoners and dissenters.

Like many others, I associate the island with Nelson Mandela’s 27-year imprisonment under the apartheid government. Mandela spent 18 of those years on Robben Island. After the collapse of the apartheid regime, the prison was transformed into a museum in 1997, and Robben Island was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, a fitting designation for such a historically significant island. Visitors can book a tour and encounter its storied past, which is precisely what I planned to do on a pleasant autumn day.

It was the beginning of autumn, which meant that the weather was cooling from scorching heat to pleasantly sunny days. I checked the time when the cab arrived — half past seven in the morning — and I was going to make it for the 9 a.m. tour. From what I had gathered, mornings were the best time to visit, as they tended to be less crowded. The ferry would not board for another half hour, so I opted to wander around the area, pondering what sights awaited me on the other side.

As the ferry launched from land, the wind picked up and its icy teeth bit into my bones. The weather was unpredictable, and visitors should dress for all kinds of conditions. As I pulled my jacket tighter around my body, I thought of all the prisoners for whom this ferry ride had been their last taste of freedom, even life. Nearly thirty minutes later, we arrived at Robben Island. As I alighted the ferry, I was greeted by the same sight that ex-political prisoner Ntando Mbatha described as a cluster of “grey buildings, dull and dim”. The island consists of several areas and buildings, including the maximum-security prison where Nelson Mandela was held, the lepers’ graveyard, staff housing, places of worship, limestone quarries, and the house where Robert Sobukwe — a revolutionary and Pan-Africanist — was held for six years in solitary confinement from 1963 to 1969 under the notorious ‘Sobukwe Clause’: legislation specifically created to extend his imprisonment indefinitely after his initial three-year sentence expired.

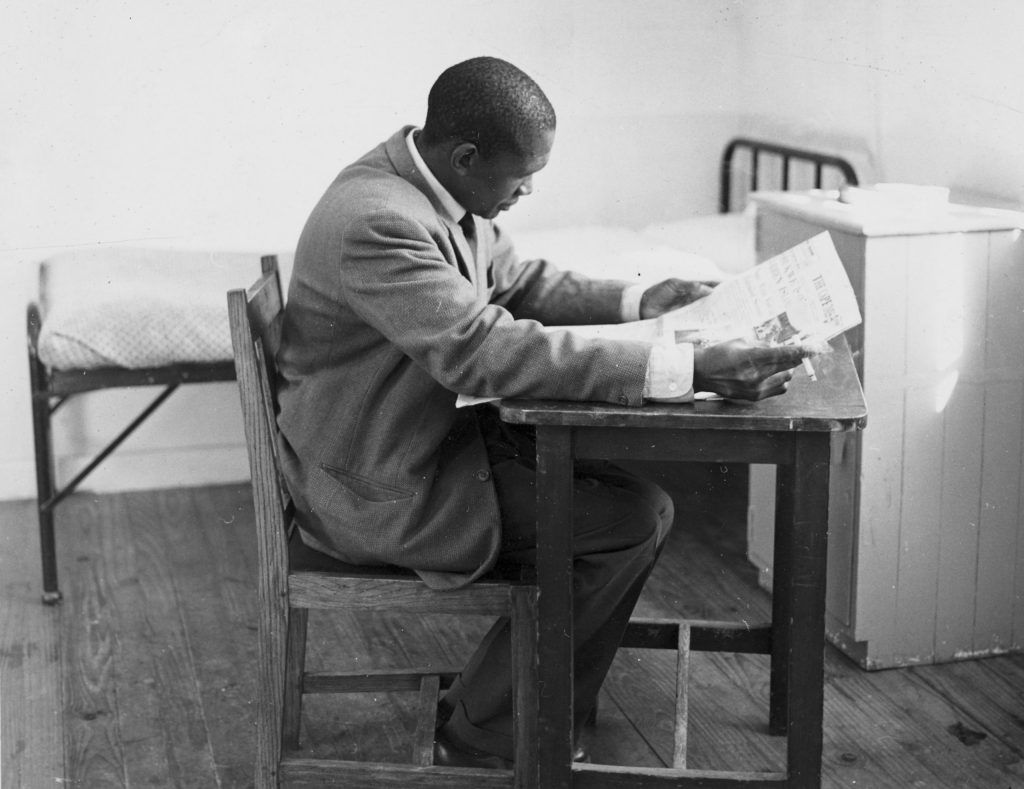

Even in prison, inmates were given different benefits based on their race. Black inmates were deliberately given less food than their coloured counterparts.

We were directed to the buses that would shuttle us across the island. Our guide welcomed us with a brief overview of its history. The mood was sombre as we began the drive. “There are three prisons on the island,” he explained. The Ou Tronk (old jail), the Zink Tronk (iron jail), and the maximum-security prison or apartheid prison built by Black political prisoners in the 1960s.” As he spoke, I was surprised to learn that he had once been imprisoned on the very island that he now walked across with authority. In fact, several of the guides are former political prisoners. I marvelled at his resilience.

The guide pointed out the lepers’ graveyard, the quarries, and the house where Robert Sobukwe was held, separate from the rest of the inmates. Despite the gravity of the scenes, sightseers crowded around with cell phones and cameras angled, a contrast that made me wonder how much of our freedoms we take for granted when this entire tour would inevitably be reduced to an Instagram story with smiling faces.

We drove into Robben Island Village, and our guide explained that the houses were once occupied by prison staff during the apartheid era and are now home to museum staff. We then stopped by a small, white, Cape-Gothic-style church called the Garrison Church, which was built in 1841 with prison labour. Our guide informed us that the museum allows couples to get married at the church on Valentine’s Day. This naturally drew lots of laughter from everyone on the bus.

Eventually, we stepped into the cool, dim entrance of the maximum-security prison — my main reason for taking the tour. Our footsteps echoed in the halls as our guide, another former prisoner, walked us through the chilling histories held within the heavy stone walls.

Opponents of the apartheid government and members of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) were held here under the ruthless regime. The Internal Security Act of 1982 built upon earlier laws like the Riotous Assemblies Act and Terrorism Act, essentially giving the apartheid government carte blanche to lock people up, break up meetings, and shut down any organisation that dared speak out. The Security Act allowed authorities to detain people without trial, ban public gatherings, and restrict organisations and publications.

Stanley Motimele, an ex-political prisoner, had his incarceration marked by losing contact with his family and comrades. He and hundreds of others were placed in isolation with no visits or contact with family or inmates, sometimes going months without speaking to anyone. “In my case, I went for a period of 10 months, and during that time, you go through a very painful and intensive interrogation process. Physical attacks on the body, psychological attacks…”

As we were taken through the halls of the prison, I learned that it was divided into sections that separated prisoners of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) from common-law prisoners and solitary confinement cells.

Our guide explained that the prison initially used a grouping system, with the lowest group being Group H, deemed the most dangerous and therefore the least privileged. ‘Good’ behaviour promoted you to a higher rank until you eventually reached Group A. Prisoners in Group A were allowed to study, purchase censored newspapers that had all political content removed, and receive — also censored — letters from their loved ones. Conditions in the prison were brutal and inhumane, but unbeknownst to the apartheid government, they would inadvertently build the very army that would pull it down.

According to former political prisoners, the revolutionary spirit in the prison was powerful. They strengthened each other and interacted with leaders of the liberation movements. Leaders were made and groomed within these walls. They mentored each other, had peer discussions and continued to build the movement from inside. They took their imprisonment as training to be soldiers, because they were fighting for the freedom of everyone.

As I took in the communal cells where the prisoners slept, I realised that not even confinement broke their spirits. In the 1970s and 1980s, prisoners protested prison conditions through hunger strikes, which ultimately led to the abolition of the grouping system and improved access to better food, recreational facilities including board games and sports, and educational opportunities such as academic classes and peer discussions, all while cut off from civilisation and news from the outside world.

Finally, we were shown Nelson Mandela’s cell. Brown blankets were folded neatly into a corner, a green table with a silver plate and cup on top, a faded red bin with a lid that functioned as a toilet, and a singular tiny window in the middle of a little room — this was Nelson Mandela’s cell. We were not allowed to go inside, so everyone took pictures of the cell from the outside. Silence fell in the corridor as we took in Mandela’s cell, only broken by the occasional click of the camera.

Once imprisoned, prisoners were forced to do hard labour extracting lime from the quarries and building the prisons and structures that would later hold them.

The tour of the prison had no formal end; we were merely instructed to head back to the buses that would take us to the ferry, much like being released from the prison. No fanfare, no farewell committee. Just due process — and stepping back into the sunlight, changed. As we drove back, the silence at the end of the tour was apt, inviting visitors to ponder the history of Robben Island. On the ferry back, I felt an immense sense of gratitude for having visited a place of such great historical significance, a symbol of great hope and resilience.

Tips:

- Book your ticket via the Robben Island Museum website, through a tour company or at their offices at V&A Waterfront.

- The Museum offers four daily tours, weather and demand permitting, at 09:00, 11:00, 13:00 and 15:00. Each tour takes 3.5 hours, including the return ferry trip.

- The museum is a registered not-for-profit organisation and relies on donations, contributions and sponsorships to sustain its growth and maintenance.