For Zambia, with Love.

Kenneth Kaunda at 100: A Tribute

There is something to be said about names. Zambia is named after the Mighty Zambezi river, Nzambi Enzi, that flows for 3,540 kilometres through the butterfly-shaped nation. I have always been curious about names as self-manifested prophecies that make us who we are. My younger brothers are a set of twins whose respective names mean love; a name reflective of an era in our parent’s marriage. I often wonder if people named Misozi weep or those named Mabvuto struggle.

“For a long time, I have led my people in their shouts of KWACHA (the dawn).”

Descriptive names are good, prophetic ones are even better, traditional praise and ancestral names can be both powerful and moving. The most comical are the strange names popular in the Eastern Province and our neighbour Zimbabwe where it is usual to find a person named Crankshaft, Covid, or Godknows based on the events surrounding their birth.

My own exploration of identity started in Grade 1 with Mrs Moonga, our class teacher. She kept a pitch black, neat afro and persisted until we learned to write our names on our books. With a shaky hand I reproduced what I’d been taught. As I wrote my name, the fragments of my identity came together as I understood my place in the family, community, school and ultimately, my nation. Mrs Moonga taught us that we lived in Zambia and our first president was Kenneth Kaunda. Because of what he had done for Zambia, his name meant something.

Kenneth Kaunda was born on April 28, 1924, in the remote village of Lubwa in Northern Rhodesia – Zambia was not born yet. The youngest of eight children, he was the son of a schoolteacher and a preacher, which instilled in him a deep sense of purpose, service and moral fortitude. My grandmother was also born in 1924, through her I learned that people born before Independence Day were subjects of the British Empire. This was a fact she tossed around with flair to explain her addiction to hot tea and Shakespeare. There must have been something transformational about Kaunda because he chose to challenge at a time when many conformed. His daring spirit changed what it meant to be a person in Northern Rhodesia and made it a place that would become Zambia.

“We have been shouting in the darkness; now there is the grey light of dawn on the horizon and I know that Zambia will be free.”

There are photos of Kenneth Kaunda as a toddler and because I know the man he would become, I can see the determination and resilience in his furrowed brow. Kenneth Kaunda emerged as a beacon of hope and resilience blazing the trail for humanitarians and freedom fighters in the region. Educated in a mission school, Kaunda was a keen learner who absorbed the principles of justice and equality, fuelling his passion for independence. His journey from a schoolteacher to a relentless freedom fighter saw him endure imprisonment and hardship, but his unwavering commitment to his vision never wavered.

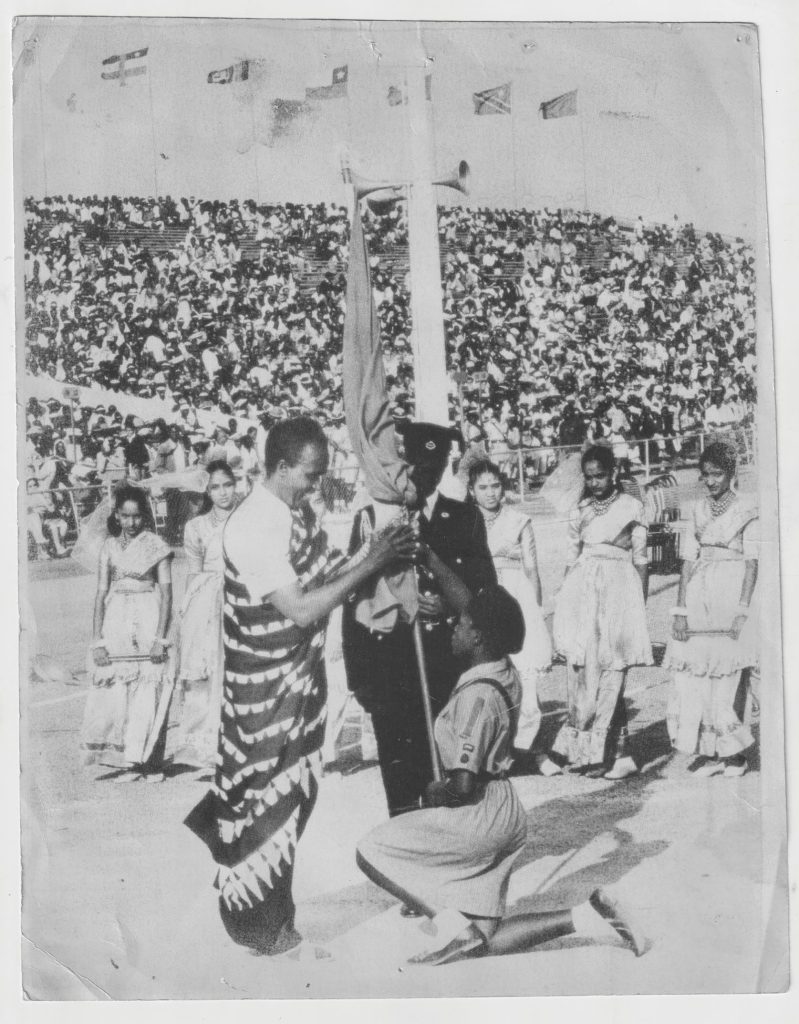

Kaunda’s vision of a united, peaceful nation steered the country through the tumultuous waters of post-colonial Africa. People of the Kaunda age have a flavour to them – a stubbornness, a severity, a steadfastness, a pride and a fire. That is who they had to be to break the chains and decide what would become of their land. While Kaunda is the flag bearer of the strength needed to take our freedom and decide our identity, many brave men and women gave up their lives for the cause. They showed up armed with faith and the courage of the nameless to make decisions we still live by/with today. With no template in place, they agreed on a name, a flag, a national anthem, a constitution, a sharing of power, a currency that would replace the pound and speak of a new day for all generations to come – Kwacha.

My little primary school was in town and my older sister, Diana, would take my sticky hand into her warm one and lead us across Ben Bella road into the depths of town – Lusaka Central Business District. I figured out that Cairo Road was named after the capital of Egypt and Cecil Rhodes’ ambitions of linking the colonies from end to tip. Before 1924, Cairo Road was known as “The Front Street” and still embodies the same spirit of activity and forward business.

Nation building is not a one-man job, even as a child I understood this and rationalised the ceremonious intent of Lumumba Road and further in the city, Haile Selassie and Thabo Mbeki Road – the first boisterous, the next celestial and the last eloquent and urban, embodying the essence of the men of which they were named.

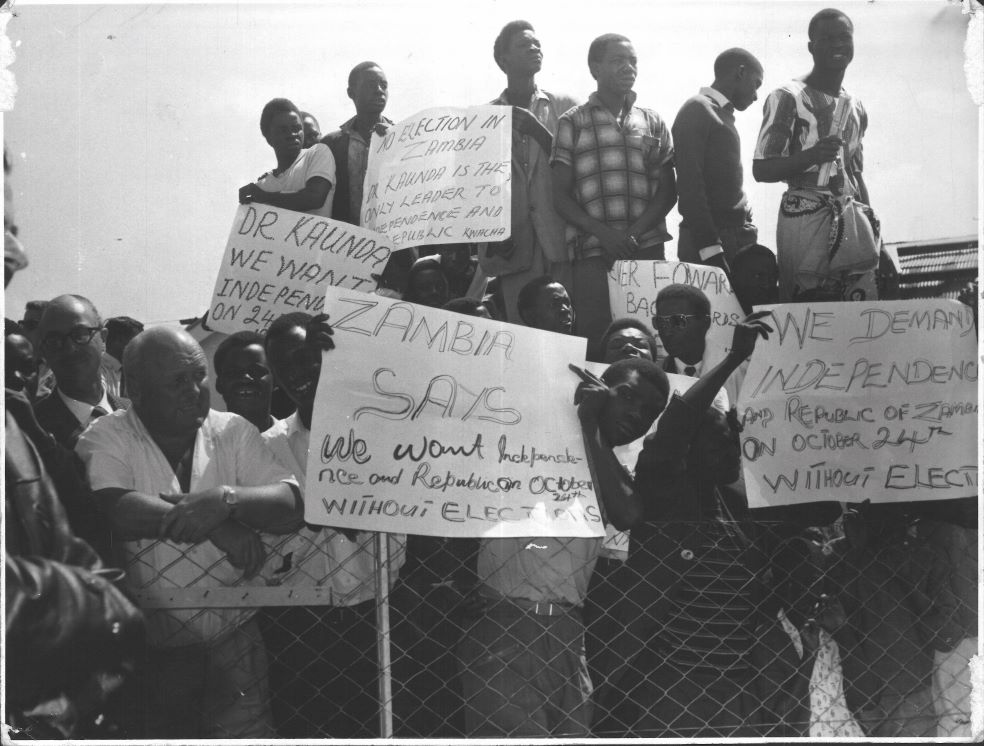

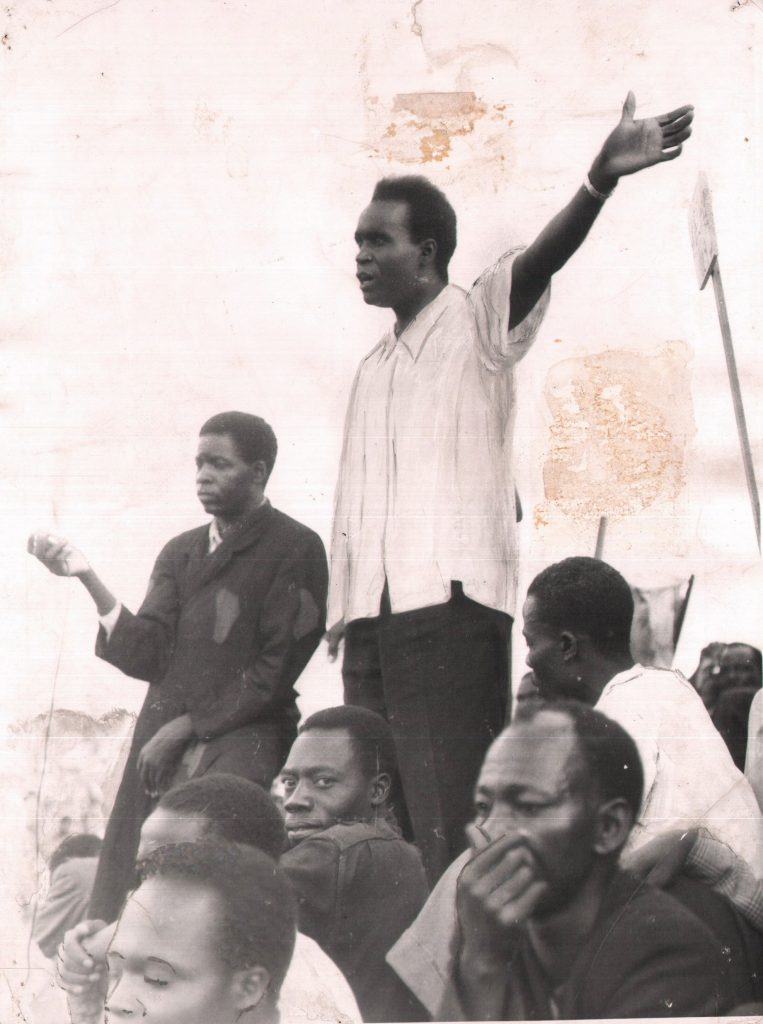

Learning about ChaChaCha and Freedom Way changed the steps I took on their grainy tar. In 1961, discontent and unrest led to a civil disobedience campaign headed by Kenneth Kaunda across Northern Rhodesia that included strikes, arson, road blocks, protests and songs of freedom by freedom fighters to express the oppression of the colonial system. There’s a sense of danger and calculated drama from the name of the campaign whose origin is the Cuban dance – the Cha Cha. Subsequently, Kaunda ran for president of UNIP in 1962 and became the president of the United National Independence Party (UNIP) which would eventually lead Zambia to independence. It was time for the colonialists to face the music.

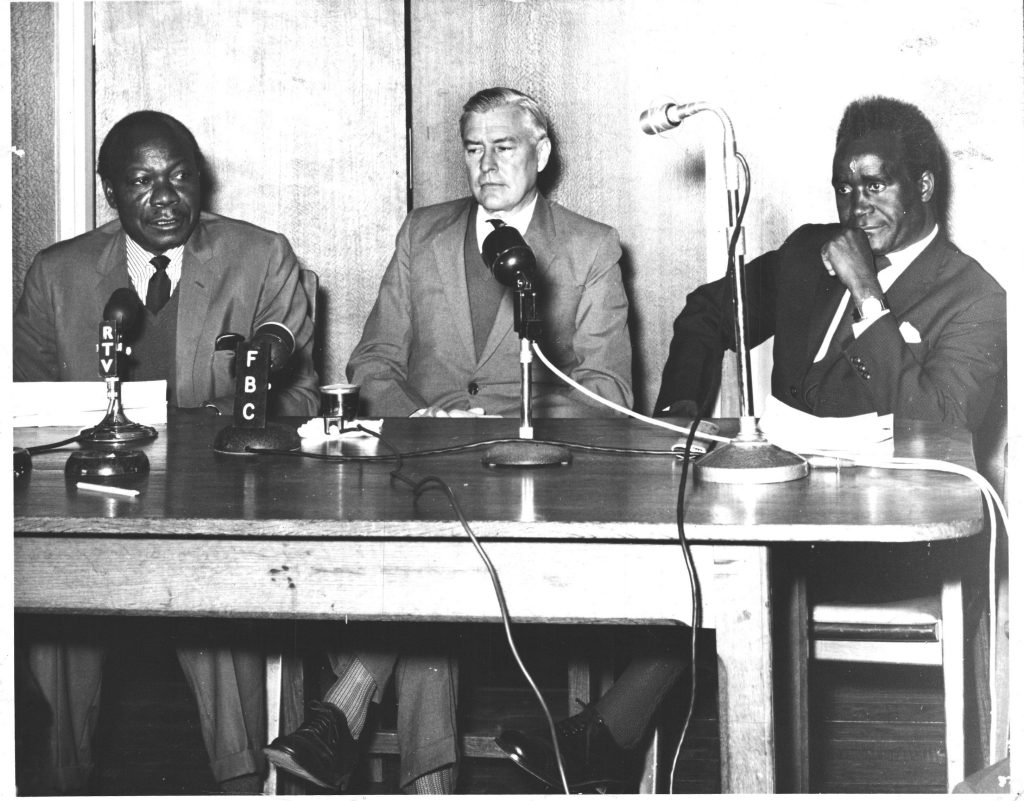

The years leading up to 1964 were devoted to tactical negotiation, partnership, foresight, and the culmination of human will, divine intervention and fate combined. We know of the arrests, shortages, hunger, and friendships that came together only to fall apart. We see the evidence of concessions, agreements, pleas, and handshakes. We know of Betty, the children, the guitar, the old house in Chilenje. We know of the iconic hair, the signature suit, the white handkerchief, and the flair. We hear of the first cabinet of young nationals eager to make their mark and form this new nation, Zambia. All the facts of the freedom struggle have become lore but they were real, with real people that made sacrifices that changed the future we now live in.

In 1964, Kenneth Kaunda was forty years old. Life began as he received the Instruments of Government on 24th October, a position he would hold for 27 years. Under Kaunda’s leadership, Zambia saw significant developments. He championed education, establishing numerous schools and universities, including the University of Zambia. His policies emphasised self-reliance and humanism, focusing on social justice and equality.

“If a government cannot be run without demoralising so badly its own people, then that government is no good and it must give way to people who can.”

Many firsts followed in an era of hope and self-ownership. Kaunda championed human rights, regional unity, and economic independence, laying the foundation for a nation rooted in unity and dignity. Dr Mainga Mutumba Bull became the first Zambian woman to hold a PhD, the first Zambian woman to lecture at the University of Zambia, and the first Zambian woman to serve as a full Cabinet Minister in Zambia. John Mupanga Mwanakatwe scored several firsts as the first African in the country to head a secondary school, first Zambian to obtain a university degree, and the first Minister of Education in the post-independence cabinet in 1964 . Many outstanding Zambians rose to form and embody the new identity of the nation. Zambia blazed a trail of freedom that many nations followed. Carrying our great name on his back, Kenneth Kaunda stood with them as they fought for the future.

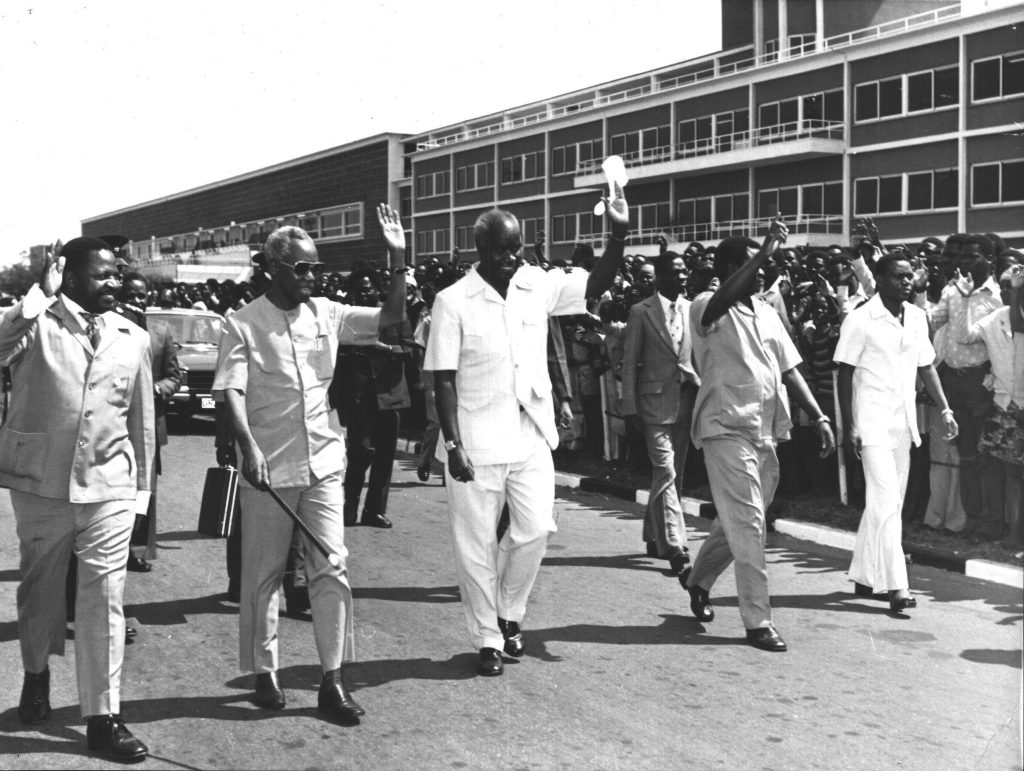

Even after stepping down in 1991, his spirit of service continued, advocating for HIV/AIDS awareness and peace across the continent. Kenneth Kaunda passed away on June 17, 2021, at the age of 97, leaving a legacy that resonates deeply with the Zambian spirit—one of resilience, compassion, and unwavering hope. Kenneth Kaunda loved Zambia as one does when they create something: fiercely.

Kenneth Kaunda’s legacy is not merely confined to the history books, it is living and evolving. His remains a figure of unwavering conviction and faith in the power of unity and love. The white handkerchief, a resounding message of peace and humility.

As Zambia celebrates 60 years of independence, Kaunda’s centennial calls us to remember the spirit that shaped our nation, reflecting on his life’s work which intertwined with the fabric of Zambia’s journey towards self-determination. As we remember the great work, let us not forget the simple things.

As Mrs Moonga taught me in Grade 1, these are the simple things:

Red represents the struggle for freedom;

Black, the people of Zambia;

Orange, the mineral wealth;

Green, the abundant natural resources;

The Eagle in flight symbolises our freedom and the ability to rise above every challenge.

Identity is fluid but if we stand as the free men we are, the choice belongs to us – we decide who we are. This year, let us be proud of how far we have come and how much further we can go. At 60, what does it mean to be Zambian? It means choice. We are the people that decide. Kaunda loved Zambia. In my opinion, his fierce love was why he couldn’t hand her over to anyone unwilling to fight for her. In 1992, the people fought with their votes and today, they continue to and Zambia’s democracy is its most charming quality.

Whenever we forget, we should remember that to be Zambian is to be as easy going as a river and as forceful as its waters.

“In those early days of our struggle, our vision was clear. We were not merely seeking political independence; we aspired to instil a sense of dignity and pride among all Zambians. The colonial era had inflicted wounds of humiliation, and it was our mission to heal these wounds through unity and national pride.

Our strategy was one of non-violent resistance, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi. The ChaChaCha campaign was a manifestation of this belief. It was a time of great sacrifice, where men and women, young and old, rose to reclaim their birthright. We faced arrests, endured beatings, and many of us were imprisoned, but our spirits remained unbroken.

“When people understand a cause, become prepared to suffer for that cause and see glory and honour in such suffering, it is indeed just impossible to suppress them or the cause they stand for.”

I vividly remember the nights spent in cells, the cold, and the darkness. Yet, in those moments of solitude, my resolve only grew stronger. It was in those times that I realised the true essence of leadership – to inspire hope in the face of despair. My guitar was my companion in those lonely nights, a symbol of hope and resistance.The unity we forged during those days was unbreakable. We were a mosaic of different tribes, cultures, and languages, yet we stood as one. The struggle for independence was not just a political movement; it was a cultural renaissance, a revival of our heritage, and a reclamation of our identity.”

Kenneth Kaunda: A True Zambian Hero – Wenguss Khan

5 months ago[…] Kenneth David Kaunda (1924-2021) was many things: a musician, an entertainer, a teacher, but above all else – a […]