Building Lusaka

In the beginning, there was Lusaka, and the spirit of progress hovered like dust over the city.

One Monday in the 90s, a deep brown baby was swaddled in a knit shawl and carried from the birthing cot at the University Teaching Hospital to a one-bedroom flat in the high-rise flats of Kabwata. Political shifts led to privatisation, which led to opportunity, and her parents bought a two-bedroom flat in Kabulonga. The street on the elbow of a crescent off Roan Road became her first home. Kabulonga is lined with roads named after large African antelopes and pink bougainvillea flowers. She took her first steps there, gained siblings, and a fluffy dog named Fluffy, of course.

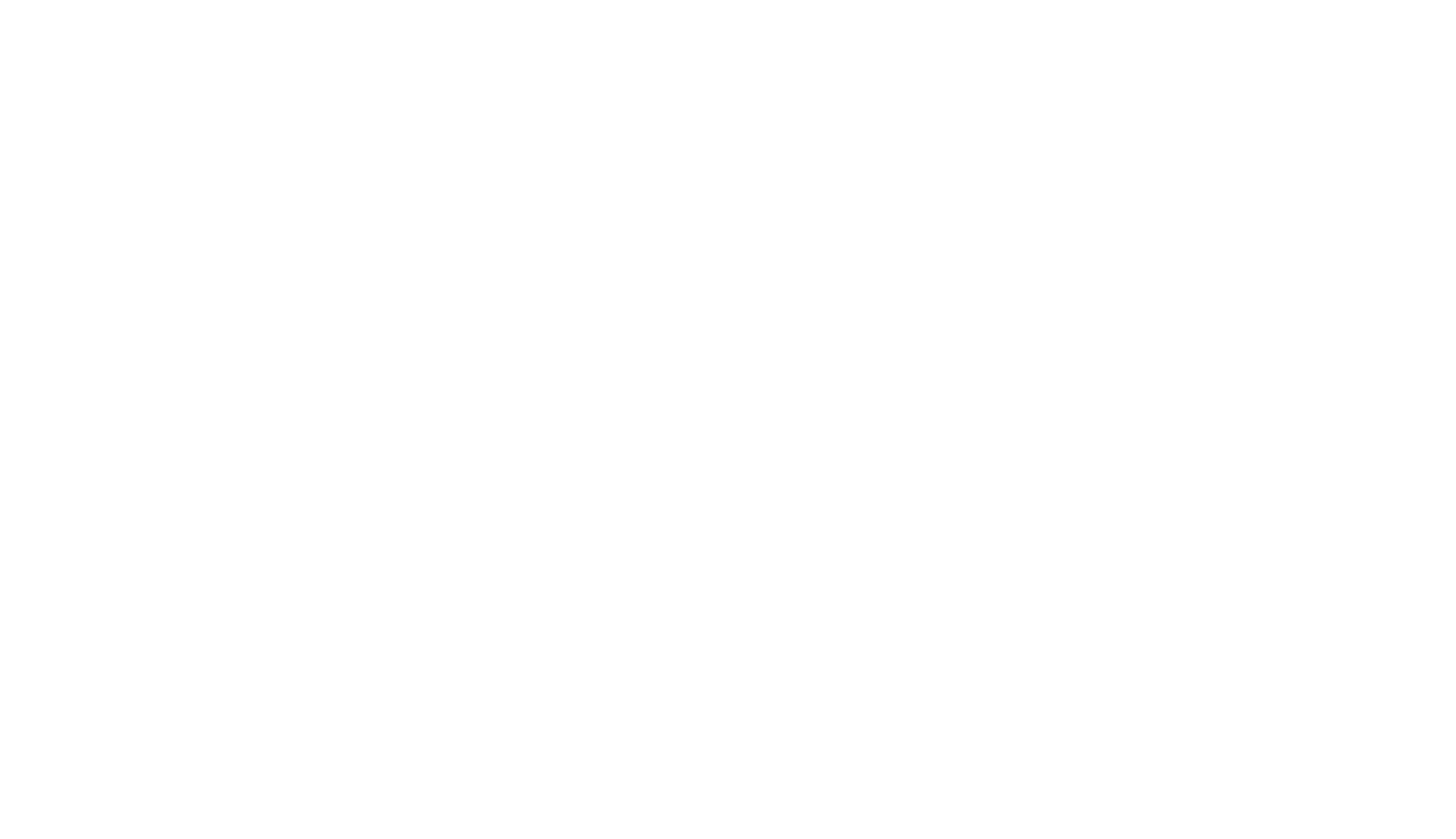

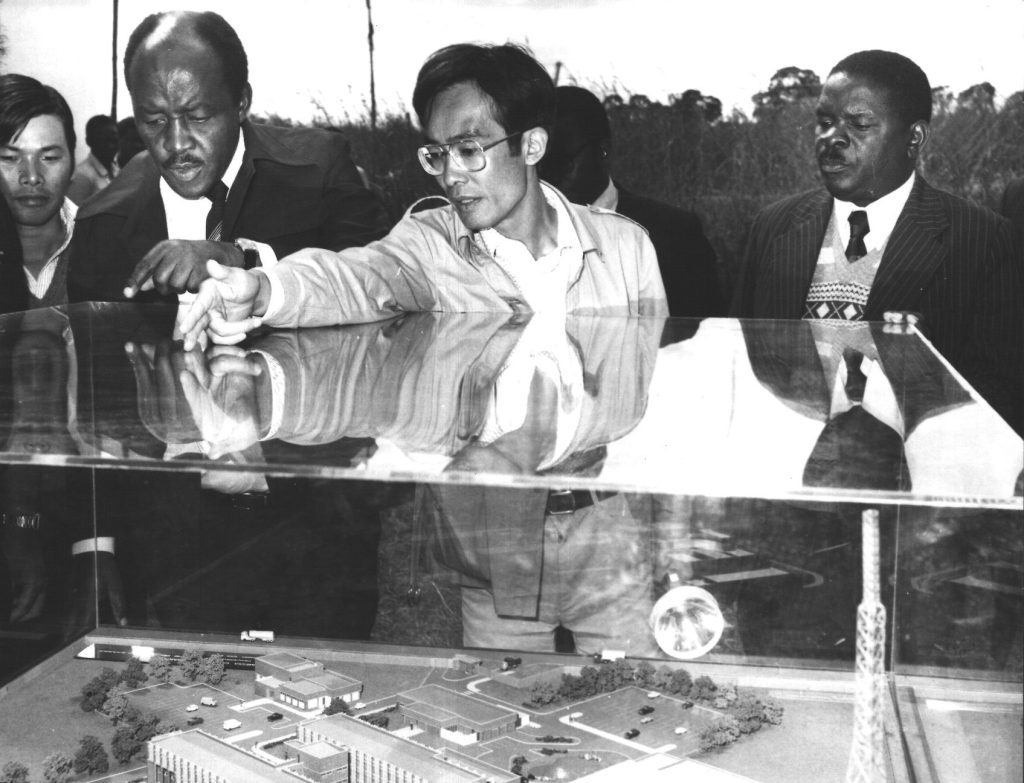

The Tanzania- Zambia Railway Authority was established in 1968 and by October 1970, track-laying had commenced. In a partnership between China, Tanzania and Zambia, the tracks from Tanzania met at Kapiri Mposhi in June 1975.

The rising pubescent population prompted a migration to Chalala, a budding suburb similar to the likes of Salama Park and Silverest, but for the middle class. These would give Lusaka a new face and a new story, and that suburb became her second home. She went to school in town, graduated from the University of Zambia, and called a few new places home until she settled. With time and chance, she returned to her first home in Kabulonga, where she now lives alone.

For clarity, that baby is me.

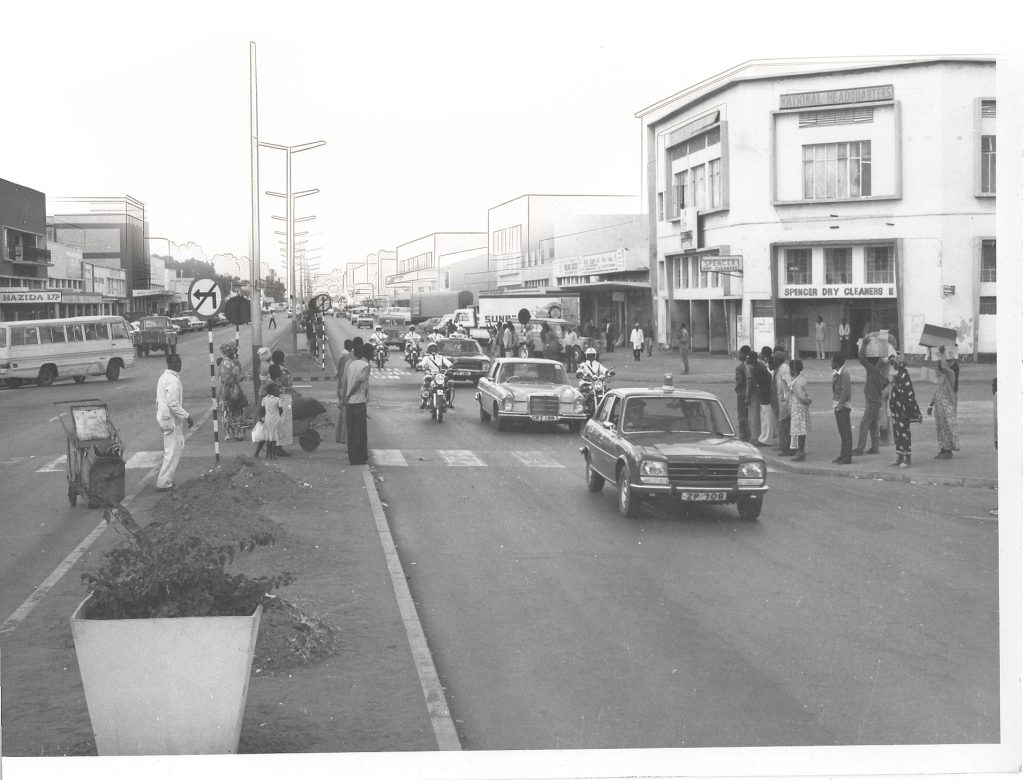

Like the lines in my palm, I can trace the roads in Lusaka and point to relics of a time passed. Blockbuster at Kabulonga Complex had the only clear VHS copy of Mrs Doubtfire (1993), and a polite man sold ice cream outside on hot days. Tontos Bakery sold sweet bread in the shape of a crocodile, and I walked across Ben Bella Road to peer into the windows of Ellerines and Supreme Furnitures at Kafue Roundabout. Chilumbulu and Burma Road had many more trees and fewer lanes, and Lusaka’s buses were blue and white without the orange stripe. In that time, Old Leopards Hill Cemetery was all we needed. There was a farm with orange trees next to it; that farm is now Leopards Hill Memorial Park, and my father rests there now.

Trapped in sentimentality, it is easy to feel like everything has changed, but some things have stayed the same. The trees around Lusaka Girls still shed purple flowers from the old jacaranda trees. Time is chasing us as we chase it.

Zambia Railways was Kenneth Kaunda’s dream for Zambia’s self-reliance and pan-African connection.

Recently, on a ten-day work trip, homesickness found me. It was strange because I live alone. Isn’t anywhere I am automatically my home? I looked within for my answers and found that what I missed were things I couldn’t carry in my suitcase. The mix of words, the familiar beggars, the traffic lights I knew would not work, the sense of inevitable victory in a salaula negotiation, and the possibility of bumping into a deal or a friend. I missed Lusaka—its dust, garbage, madness, and hope.

But What Even Is Lusaka?

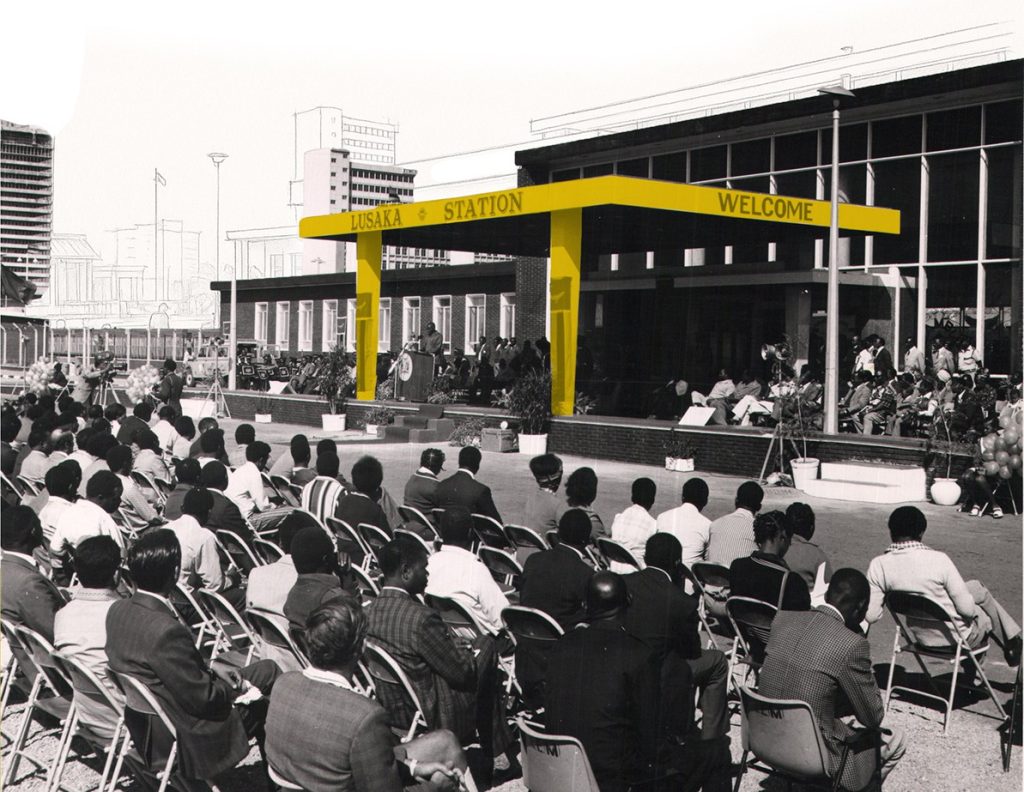

Indigenously inhabited by the Lenje and Soli people, the patch of land had the paradoxical fate of being ideally situated for a railway stop to fulfil John Cecil Rhodes’ dreams and the British South Africa Company’s ambitions in 1905. In 1913, Lusaka became an outpost for administrators and farmers. Named after Chief Lusaaka, its central location and pleasant weather earned the city favour over the famously beautiful Livingstone, making it Northern Rhodesia’s capital in 1935. This was long before independence in 1964, when the dream of Cape to Cairo was still alive.

Post World War II, Lusaka’s position as an administrative and commercial hub drew all seeking to create better lives. Nicknamed ‘The Garden City,’ pre-independence Lusaka was lush, manicured, and built for functional colonialism. Fossils of segregation whisper in the names of its buildings, roads, and wrought iron finishings.

While I was away in the trenches, eyes glimmered when I said I was from Lusaka. Home to the tallest building in Zambia, the largest university, and the most advanced hospital, Lusaka means something.

Lusaka was the platform for the civil unrest that led to the birth of the Republic of Zambia, of which she would become the capital. But is Lusaka even a woman? Lusaka has beauty, but what makes a city a man? Its ability to endure. Lusaka has that too. Lusaka is a genderless, shrewd body, taking up the form required for survival. While the bones of colonialism still hold up the structure of the city, Lusaka has a mixed economy where anything is made and sold, with rail and road routes threading through and beyond the city. Leading in population, development is spreading out of the province, but as the capital, all things happen through Lusaka.

There is an old joke about a rural man who arrived in Lusaka City, only to be scammed by the kaponyas into paying a fee for looking up at Findeco House—the tallest building in Zambia. Officially opened in 1978, it still carries, behind its smog-covered copings, the glamour and awe that might make someone fall for such a scam. Described as ‘brutalist modern’ in style, most of Zambia’s post-independence buildings share a similar form: stark, unapologetic structures that prioritise function over form. Findeco House, the University Teaching Hospital, and the University of Zambia are a snapshot of the sovereignty rush and optimism on which the city was built.

I can imagine Kenneth Kaunda standing in his suit, dictating the strict deadline to the Yugoslavian architects of Energoprojekt, who would go on to build a structure where 62 heads of state would gather under one roof. Mulungushi International Conference Centre was delivered two weeks shy of the deadline, symbolically pointing to political independence and the infrastructure necessary for its realisation.

Free Men We Stand Under the Flag of Our Land

Audre Lorde says that free women are dangerous women. But I argue that it is not just women; it is people. True freedom reveals one’s true essence, with an educated kindness or pure greed unshackled from subjugation. I spare my distant ancestors from judgment, but every single citizen of Zambia born after 1964 has to answer one question: why are we this way?

Freedom House was a crucial base for the United National Independence Party. It is located on Freedom Way in Lusaka and was also the headquarters of the party. It is also part of the party’s Research bureau and its archives hold some of the most important documents related to the party’s history and the early ANC party.

The architecture of our founding fathers is monumental, standing as tall as their legacies. Yet today, we seem to be taking on the form of bending kiosks, plastic malls, and wounded roads. The truth is, I am a little bit disgusted by what we have done with the Garden City, but I can’t help loving it all the same. I get homesick for Lusaka because it’s the only place on earth where I can tell where someone was raised simply by their choice in jeans; the only place where we all complain about service providers but never leave; the place where Lukundo Lite, Pa Chimutengo, and Yellow Shop have become designated names for their neighbourhoods; the only place where jokes about dusty areas are still funny.

It’s the little things—things like discovering that 6, 10, 13, and 16 Miles are named thus because of their distance from the original heart of Lusaka: the rail line next to the Post Office.

Kwacha House in Lusaka, currently houses the Ministry of Tourism and is a prominent example of Brutalist architecture in the city. It was completed in the 1970s and is known for its distinctive style.

Living in the house where I was raised has placed me in an era of peace and acceptance. I walk like my father, and I am ageing like my mother. It is hard to fight familial identity and geographical DNA. Maybe Lusaka will always be this way because we are this way. Maybe where we can’t subtract, we must add. We can add direction to our innovation and build a future reflective of us.

Lusaka is home. A place where I have the right to hate both the place and its people, with context, to rename things with a nickname others will share. A place I can’t smell, a place with stray dogs I know, and beggars who know my mood on pay day. In 1935, they played British music. Now, in 2025, it’s Yo Boy on every corner.

Lusaka is home. They created it for them, but we made it ours.