After the Dream

“In our daily life, most of the things we use are imported. The food we eat, the utensils we eat from, the clothes we wear, the chairs we sit on… all come from outside Zambia… We have completely adopted a foreign culture.”

These candid and, yet, disturbing words came from Zambia’s Vice President, Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe, in an address to the National Conference on Culture in 1969. —an excerpt from Fola Soremekun’s paper Zambia’s Cultural Revolution, 1970.

According to Soremekun, while the economic reality of Kapwepwe’s statement cannot be denied, the implication is even more profound: despite achieving political independence, Zambia’s cultural identity remained heavily influenced by foreign—mainly colonial—forces. When Kapwepwe stated that Zambians “have completely adopted a foreign culture,” he was not only commenting on the tangible effects of colonialism on everyday life but also pointing out a phenomenon that was particularly pronounced in Southern Africa, where people, whether politically independent or not, continued to live as though they were foreigners in their own countries when it came to matters of culture.

The National Conference on Culture of 1969 was a response to this problem and a defining moment in Zambia’s post-independence trajectory. Despite gaining political freedom, Zambia grappled with tribal coexistence, and economic independence remained, Kapwepwe believed, an elusive dream. The conference aimed to establish a roadmap for Zambia’s journey toward “absolute” independence, which encompassed establishing a truly Zambian identity nearly void of all colonial and European influences. It was an ambitious attempt to define a nation that would be both united and distinctly Zambian, forged through a collective consciousness shaped by Zambia’s own people and history.

At the forefront of this movement was Vice President Kapwepwe, a Pan-Africanist and anti-colonialist who deeply understood the relevance of culture during liberation and post-independence, as the most potent tool of successful colonisation is the dismantling of the cultures that define a people’s identity. The legacy of colonialism had left Zambia with a fragmented sense of self, diverse ethnic groups, mentalities conditioned by colonialism, and regional political affiliations competing for prominence. Kapwepwe understood that in order to achieve true independence, it was not enough to simply remove colonial rulers. The people had to break free from colonial influences that still held sway over their minds, cultures, and governance.

Zambianisation

The Oxford English Dictionary defines Zambianisation as ”a policy that replaces non-Zambian citizens with Zambian citizens in various occupations”.

Zambianisation and “One Zambia, One Nation” emerged as the rallying cries for this transformation, not merely as nationalistic slogans but as well-articulated policies to reshape the country’s political and economic structures. Zambianisation was born out of the need for both cultural and financial independence. Contrary to the Oxford English Dictionary’s reduction of Zambianisation to a mere transfer of responsibilities from Europeans to Zambians, it involved a much broader reorientation. It meant redefining the educational system, restructuring the economy, and reshaping the workforce to reflect the nation’s new identity. Zambians needed to develop their leaders, workforce, and industries. In the early years after independence, foreign expertise was still necessary, and Zambia sought partnerships with nations and regions that understood and sympathised with its struggles.

Few Zambians were happy about the state of African culture in their society before Independence. As cultural awareness tends to go side by side with nationalism, the fire of cultural nationalism has started to burn in the hearts of many.

– Fola Soremekun

However, Zambianisation also revealed the limitations of this process. While it was a necessary step toward independence, it was not without its challenges. Foreign experts from India, China, Yugoslavia, and Scandinavian countries—particularly Norway—were essential and played significant roles in developing Zambia’s infrastructure. Moreover, European individuals such as Simon Zukas, Andrew Sotiris Sardanis, and Steinar Bosnes, who helped to structure the foundations of the Kenneth Kaunda Foundation and the national education publishing house, underscore that Zambianisation was not a purely racial initiative. It was about replacing foreigners and building partnerships with those who understood the country’s struggles. This was one of the more complex contradictions of the period: Zambia needed to develop, but it also had to avoid falling into a state of dependency. The challenge lay in balancing external support to create an independent, autonomous nation.

On “One Zambia, One Nation”

[Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe] “The major task facing the nation…is to establish our identity and a system of doing things the Zambian way…To do things the Zambian way should have nothing narrow about it…”—an excerpt from Fola Soremekun’s paper Zambia’s Cultural Revolution, 1970.

At the same time, the slogan “One Zambia, One Nation” became a rallying cry for a more unified national identity. For Kapwepwe and his contemporaries, Zambia’s primary task was establishing a system of doing things the “Zambian way.” This was not meant to be a narrow vision. However, Kapwepwe was careful to acknowledge that Zambia’s culture could not be developed in isolation. While borrowing ideas and techniques from outside was inevitable, Zambia’s identity needed to remain distinctly its own. He cautioned, “Accepting all without discrimination is going too far.” Zambia needed to retain a cultural identity that was uniquely its own, but it also had to remain open to influences from the outside world. The balancing act was clear: Zambia needed to incorporate elements from global culture but avoid the wholesale adoption of foreign practices that could further undermine its identity.

Kapwepwe argued that cultural pride would be essential to the country’s economic development. His assertion that “Culture is Money” reflected a more profound understanding that economic growth and cultural autonomy are not separate pursuits. By creating and purchasing Zambian-made products—whether in the form of a wastepaper basket or traditional crafts—Zambians could create a unique identity and harness economic power, logically allowing the nation to retain more of its wealth. Kapwepwe’s creation of the black Chilenje shirt, which he personally designed and tailored, was one such effort to undermine colonial structures. Although banned by the colonial authorities under the pretext that it resembled Mussolini’s black shirt, its symbolic power was undeniable. Kapwepwe’s shirt drew inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi’s strategies against colonial rule in India, which played a crucial role in India’s independence. Gandhi’s promotion of Indian-made goods, including his iconic loincloth, was a symbolic and economic gesture that united the nation in rejecting colonial economic systems. Similarly, Kapwepwe believed that by embracing and promoting Zambian-made goods, Zambia could economically empower itself and break free from the remnants of colonial influence.

Despite these efforts, questions about Zambia’s true economic independence remain. Over 55 years since the Nation’s Conference on Culture, how far have we come in our pursuit of complete decolonisation and self-determination? How much control do we have over our resources and in determining our collective path and destiny? In many ways, Zambia has made significant strides in building a peaceful society. The philosophy of “One Zambia, One Nation,” along with the regular transfer of civil servants to regions outside their home areas, facilitated interactions and coexistence among people from different ethnic groups. These efforts have fostered strong bonds and created a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual nation where many Zambians are born of a combination of two or more tribal groups, creating a hybrid cultural identity. This hybridisation has the potential to be a source of strength, which Zambia can leverage for collective gain.

Culture is Money

‘He saw no reason why government offices could not use Zambian-made waste-paper baskets. Zambians could save money by making things for themselves and selling these to the Government. People ought to know that ‘Culture is Money’—an excerpt from Fola Soremekun’s paper Zambia’s Cultural Revolution, 1970.

The conversation about Zambia’s economic future cannot ignore the role of culture. As Kapwepwe wisely stated, “Culture is Money,” and Zambia’s cultural wealth is a resource yet fully harnessed. Today, the nation faces the dilemma of exporting raw materials—like copper—instead of processing them domestically to add value to its resources. As Kapwepwe envisioned, economic independence requires more than political sovereignty; it demands a complete transformation of Zambia’s financial and cultural infrastructure. The ongoing reliance on foreign markets and expertise calls into question how far the country has truly come in its pursuit of self-determination.

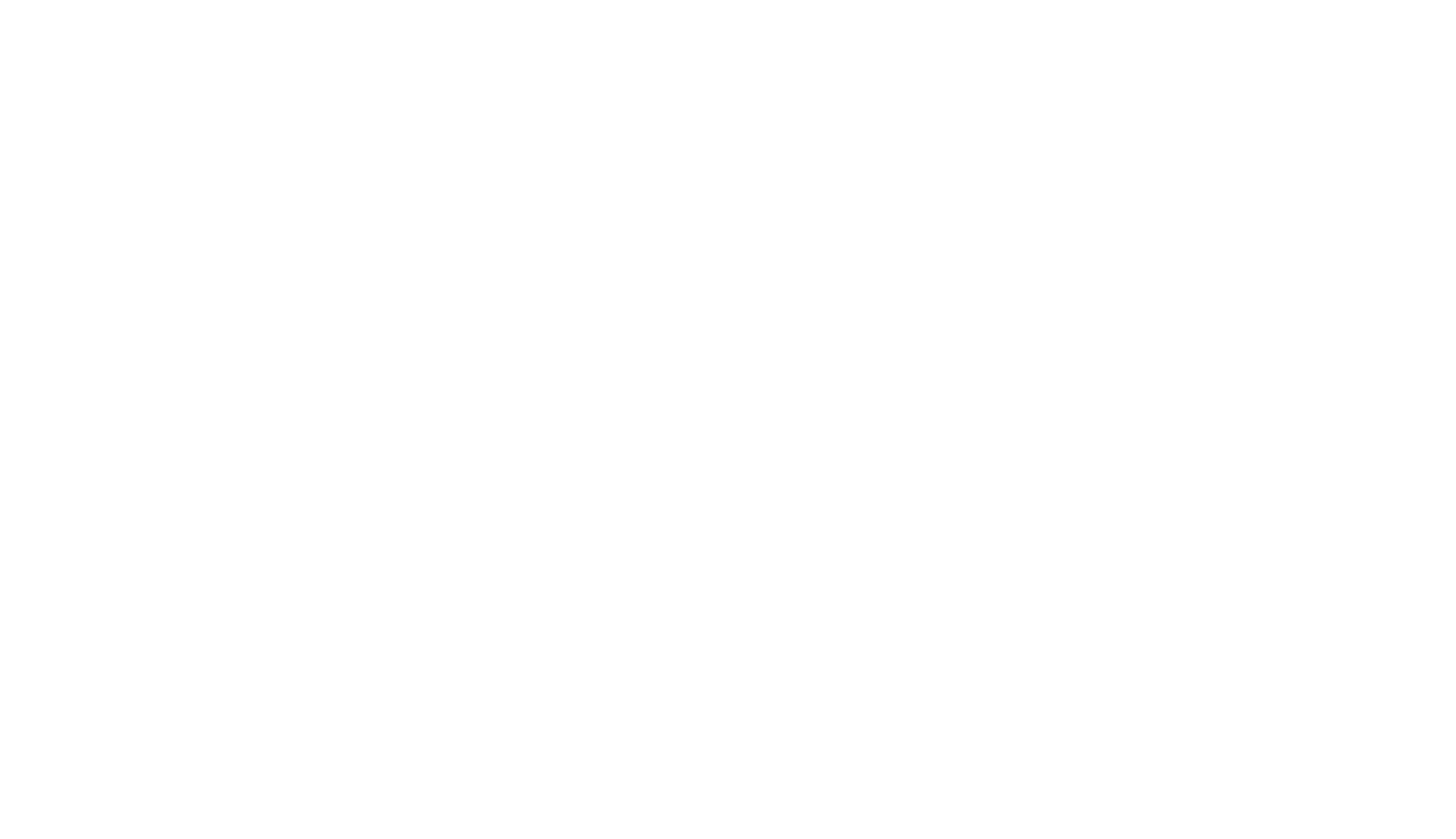

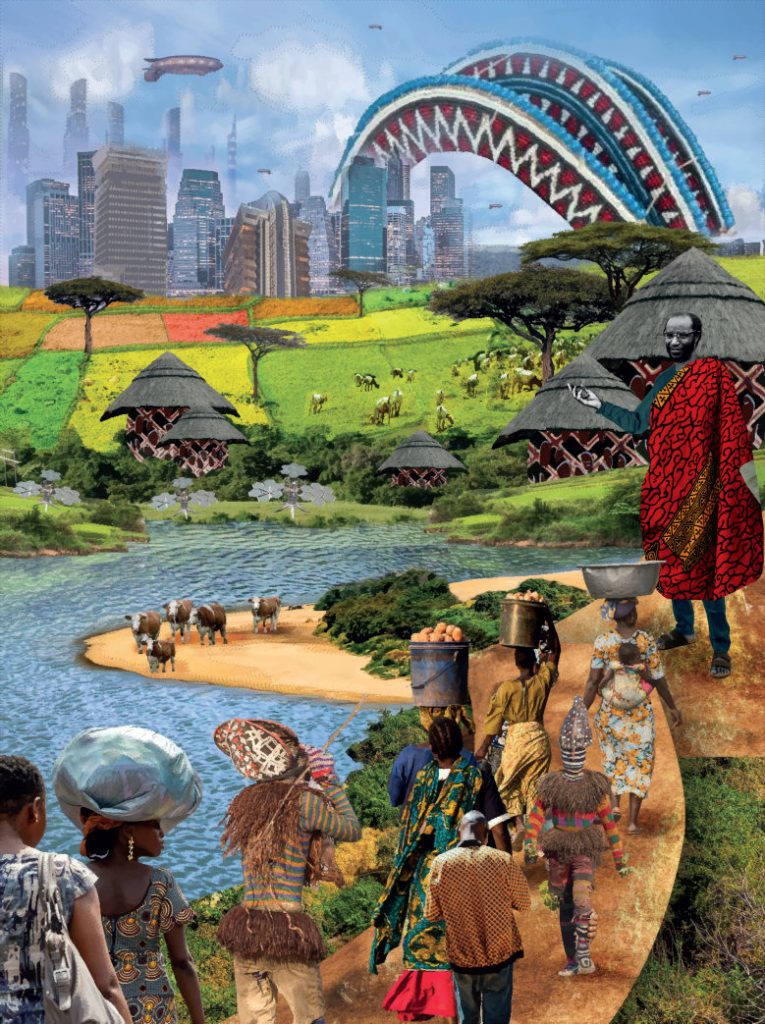

In this context, the revival of Zambia’s traditional art forms could play a critical role in achieving both cultural and economic independence. In his master’s thesis, prolific Zambian artist Godfrey Setti examined the phenomenon of ‘contemporary Zambian painting,’ noting that it is a Western imposition that began in the mid-20th century. Before this introduction, Zambia’s artistic traditions were grounded in indigenous practices like mural painting and carving, using natural materials such as yellow ochre, clay, and tree bark. These materials were integral to cultural identity and societal unity, fulfilling spiritual and communal purposes. The colonial destruction of these practices was a loss of art and a unified cultural identity.

The philosophy of Hmanism was nothing really new; Kaunda had been leading towards it in hsi speeches before Independence. The essence of Humanism, as it related to culture, emphasised, among other things, the restoration of dignity to the African person, the promotion of worthy African customs and traditions and the belief that Africa has something to give the world

– Fola Soremekun

Today, Zambia has the opportunity to reclaim and revitalise its traditional artistic practices, creating a unique, globally recognised art market that reflects the country’s identity and contributes to economic development. Reviving these practices could also help Zambia break free from the dependency on raw material exports and create a thriving, indigenous cultural economy. By fully embracing and investing in its cultural identity, Zambia can build an economically self-sufficient future and be deeply connected to its roots, fulfilling the vision of true independence that Kapwepwe and others fought for.