Witnesses of the Wild:

The Mists of Busanga

It’s like a dream,” Isaac says, looking out towards the horizon. His hands are resting against the side of the safari vehicle, a converted Toyota Hilux. The canvas-covered seats, both yellow and brown, catch the final fits of a dying sun. When it drops below the edge of the earth, so immediately does the temperature. Isaac, in a place between memories and a dream, tugs at his beanie.

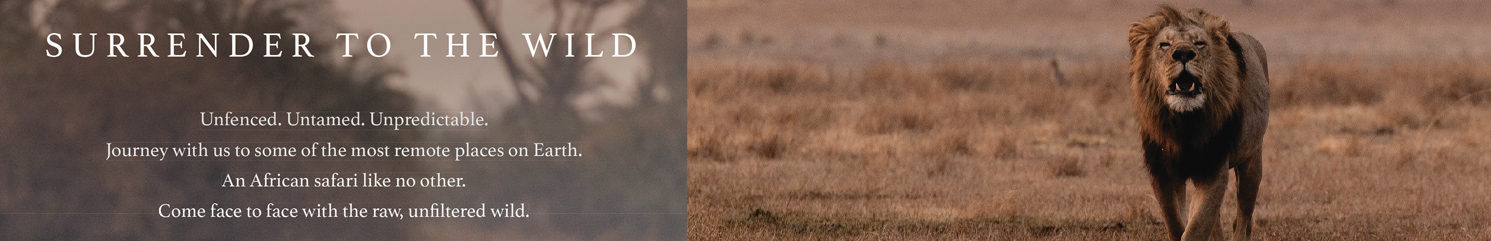

We head off to the camp, Shumba Camp, part of the Wilderness Portfolio, which overlooks the Lufupa River and a few waterways supporting a constant supply of puku and lechwe. During the day, you can watch them from the raised balconies of the tented rooms and common areas, lazily grazing on the short green grass of the river banks. Their lean bodies are like electric pulses on the landscape — almost unmoving at first, and then, without warning, they vanish into the horizon, forever fearful that they may be caught. Predators — the most numerous being lions — are never too far away. There is a radioactivity that permeates the plains: the sun rises over a carpet of mist that could as well be smog from factories, colours take on unnatural hues beyond the standard spectrum of the eye, one hears the urgent barks and whistles of antelopes that sound like industrial alarms, calling the end of a shift.

The name “Shumba” meaning “lion,” reflects the presence of thriving lion prides—sometimes numbering up to 20 individuals, frequenting the plains.

After dinner that night, we sat around the fire, a routine that would continue for the evenings to follow. The orange and yellow flames reminded me of the sunset a few hours earlier, although more contained — we fed off it in the brisk evening air regardless. Now and then, a cold wind would blow across the plains, the Milky Way following it across the night’s sky. Or maybe the wind followed the movement of the Milky Way; here, it is difficult to tell what follows what.

With his name, I imagined Evidence to be thin and wily like the law. But he is short and portly. A smile fills the width of his round face, betraying an uneasy friendliness that turns out to be genuine. At the fire, he sits down across from us and spreads his legs open, leaning forward. We, along with the fire, are co-conspirators.

The bush is filled with anecdotes. Without them, it seems we may be lost. One has to be a good storyteller to make sense of this wilderness, and the casual violence with which an animal may die, hinting at our own human fragility. Evidence’s position as manager means he orients himself towards his guests, relating their hubris and gentleness, and of national characteristics: Americans are like this, Russians like that (just don’t get them in a game vehicle at the same time), and so on. There is a worldliness to working in Zambia’s luxury lodges. And soon, like most things around a fire, the conversation drifts to politics. And to colleagues who have left ‘the bush’ to join the gold mining spree in towns not too far away. Sometimes reality mirrors fiction. By now, the Milky Way has faded, leaving only the brightest stars behind.

Busanga is teeming with big game, including predators such as lions, and cheetahs. You will also spot hippos wallowing in the shallow pools. If you are lucky, you may come across wild dogs and hyenas as well.

Isaac, our guide, joins us along with Dawid. The latter is quiet and kind. On the first morning, I turned out of bed quite ill — the long drive and a toxic admixture of gin and wine having set the world spinning. (I now understand why most people fly; we had the luxury of an eight-hour drive from Lusaka, half of which was spent on a dirt road.) With a cold, practised hand against my burning, embarrassed body, Dawid took my blood pressure and temperature.

Isaac is tall with a broad nose pointed at its end, and a short beard. Like Evidence, so too do his legs spread out in front of him to arrest what little warmth the fire gives. His beanie sits atop his head. Now and then, he adjusts it. Perhaps it is the light, but he is the spitting image of an older Thelonious Monk, the maverick jazz pianist — he has the same deep-set eyes, the same world-weariness. He complains about his back as he carries coolers out of the game vehicle. One can imagine the physical toil of guiding for 17 years, riding on makeshift or non-existent roads for eight hours or more a day.

More anecdotes. This time, on the drive across the plains. Of animals — Isaac shows us a video of the area’s resident hippo, Bubbles, being attacked by a group of lions. Some of the lions climb on Bubbles’ back but fail to take him down. He’s seen lions successfully hunt a hippo, and others killed by a buffalo. As the primary predators on the Busanga Plains, lions feature prominently in these anecdotes. Indeed, Isaac is something of an expert on the ‘lion politics’ of Busanga. Around midnight, on our final evening by the fireside, he relates the history of lions in the area — or more appropriately, he describes an intergenerational saga spanning seventeen years. Five generations, a dispersed pride, the arrival of outsiders, incest, trophy-hunted males in the concessions — all this has led to three separate males vying for supremacy of Busanga. We hear roaring at night — these lonely males. They keep me up. Midnight turns into day without thought.

Isaac shows us other videos and pictures. He has an oeuvre that betrays his many years on the plains. He has an ‘eye’ for photography, and takes damned good pictures. That is not accidental, however: Busanga requires an attitude of observation. And patience. Isaac always keeps a hand on his binoculars, which survey the field for any clues of animals, or of animals signalling the arrival of predators. It’s a trick every good guide knows. “It’s in the detail,” Isaac says, as he compares watching animals through his binoculars with watching television. “Better than National Geographic.” Which is why I imagine many folks come to these parts — to step outside of their virtual habits, for an encounter with the real.

Patience is a virtue for the guests, too. It can be a tiresome thing, looking out across the plains. Areas of long grass are punctuated by the slow movement of larger antelopes that gaze at us inquisitively. Closer to the waterways, the puku and lechwe are disturbed by our presence. We tread across the flat plains like an unwanted visitor — a dangerous curiosity. You cannot partake in this world, only observe it.

Isaac’s photographs are akin to anecdotes — the visual equivalent of I saw this and that, which is a primary reason why people spend a small fortune to visit one of the country’s most remote areas. (In our luxury tented rooms, there is a ‘species checklist’ book that taunts me every time I pass the foot of my bed — should I treat the wilderness as something which can simply be ticked off?) Of course, this attitude sustains Shumba, along with the other lodges in the area. The economics of safari lodges demand viewing wildlife as a commodity that can be harnessed to produce tangible results. (It would be remiss not to mention that there are other measures of conservation, although they are less financially rewarding.) And it is the same logic that leads Isaac to observe that Shumba “has so much potential.”

Wildlife congregates seasonally around the retreating waters: expect large herds of red lechwe, puku, roan, oribi, wildebeest, buffalo, and zebra. Come earlier in the season and you will witness young calves and cubs.

Part of this potential is the romantic allure of the bush. Words such as ‘timeless’ slip into conversations, ‘beauty’ is thrown around a little too often — but what does this all mean? There is a deep attachment to the terrain — Isaac, Evidence, Dawid, and the other staff see themselves as ‘from the bush’ now. Some of them are Kaonde, an ethnic group whose ancestors roamed the plains before the Kafue National Park was officially established in 1950. They still have access to the land — or more specifically, the water — every year, their descendants are allowed to set up their fishing weirs on the Lufupa River. In the off-season, these structures of wood and twine seem like relics from a lost civilisation.

Human history, animal history, and the ecosystem all merge into one. Isaac is part-educator and part-storyteller, somehow part of this landscape. It is difficult to imagine him elsewhere — at home in Siavonga, for example, or in his village of Chiawa (just outside of the Lower Zambezi National Park, where Isaac is the reigning Scrabble champion). He cuts the right figure as he sits atop the side of the vehicle, this time teaching us the difference between puku and lechwe. It is not a difficult lesson. But he does it diligently, handing the binoculars around to each of us — in a place so seemingly vast, the details are the first to suffer.

A standout spectacle of the plains: uninterrupted views of the sunsets, sundowners on the open plains and the guides that bring the bush to life.

“It’s like a dream,” Isaac repeats. Speaking about the plains now bathed in the orange glow after sunset, the plastic fold-out table for sundowners was just stable enough on the uneven ground below. Hippos and antelopes have created craters in the mud dried to dust in the intense winter sun. The gin goes to my head, and I smile. Yes, it’s like a dream, I tell myself. It must be.