A Thought Experiment:

What If Zambia Had Made It to the Moon?

The space race began on August 2, 1955, when the USSR responded to the US announcement of its intention to launch the first artificial satellite by declaring its own plans to do the same. On October 4, 1957, the USSR successfully launched Sputnik 1, the first Earth-orbiting satellite in history. However, on the morning of October 25, 1964, Zambia stunned the world as the first female afronaut, Matha Mwamba, was launched into space, becoming the first African country to send a manned spacecraft into space.

– Space Race Timeline, Royal Museums Greenwich

BBC World News

October 26, 1964

ZAMBIA FIRST ON THE MOON – AFRICAN NATION STUNS THE WORLD

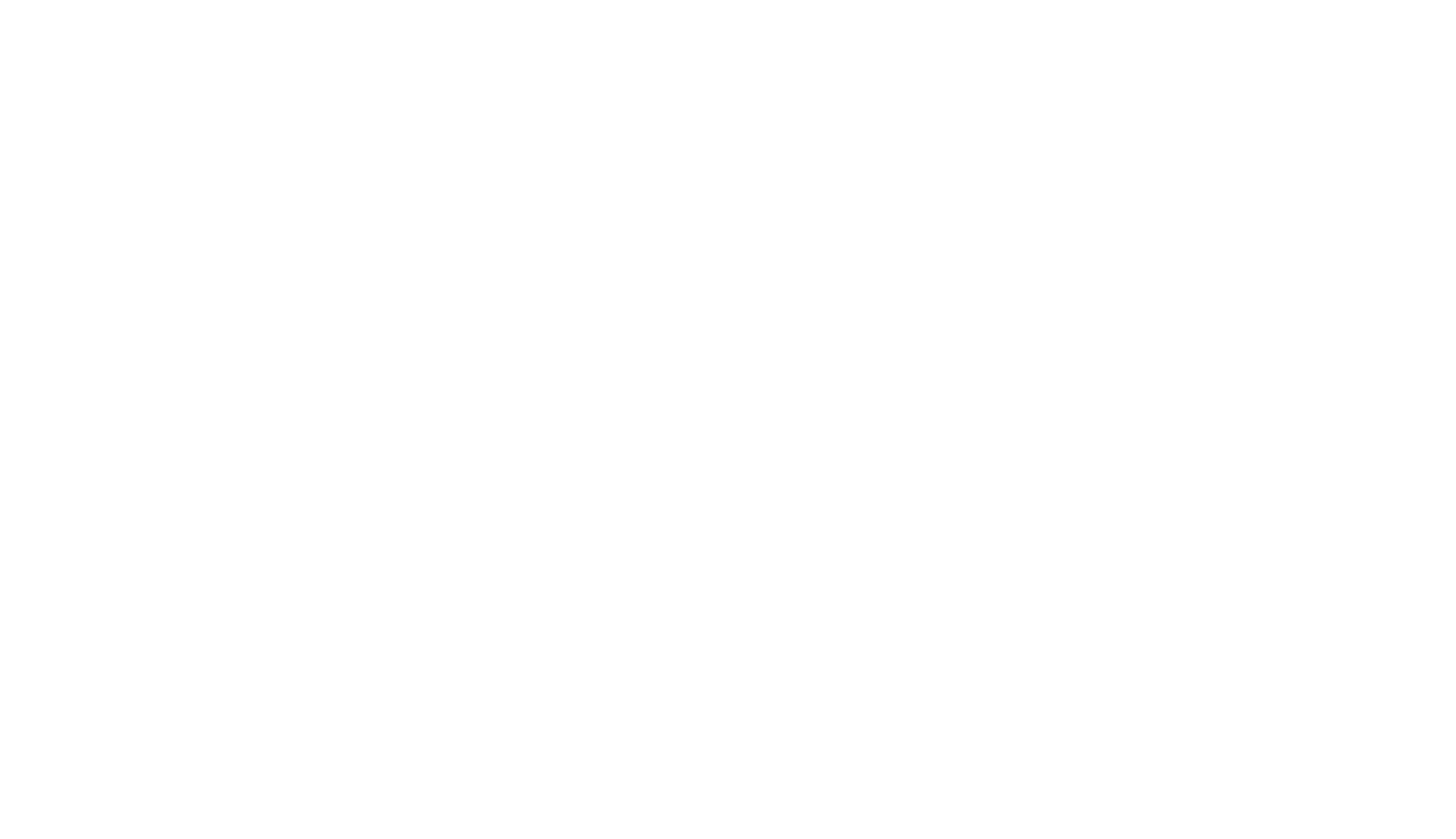

As the sun crested the eastern sky, the day after Zambia’s first Independence Day, a thunderous crack split the air above the Kafue plains. A sleek, bronze-tinted rocket—code-named Kalu-D1—emblazoned with a Chitimukulu emblem and the motto “Where fate and human glory lead, we are always there”—lifted off. Inside was Matha Mwamba, the world’s first female astronaut and the pride of a newly liberated Africa. Her mission: to land on the Moon.

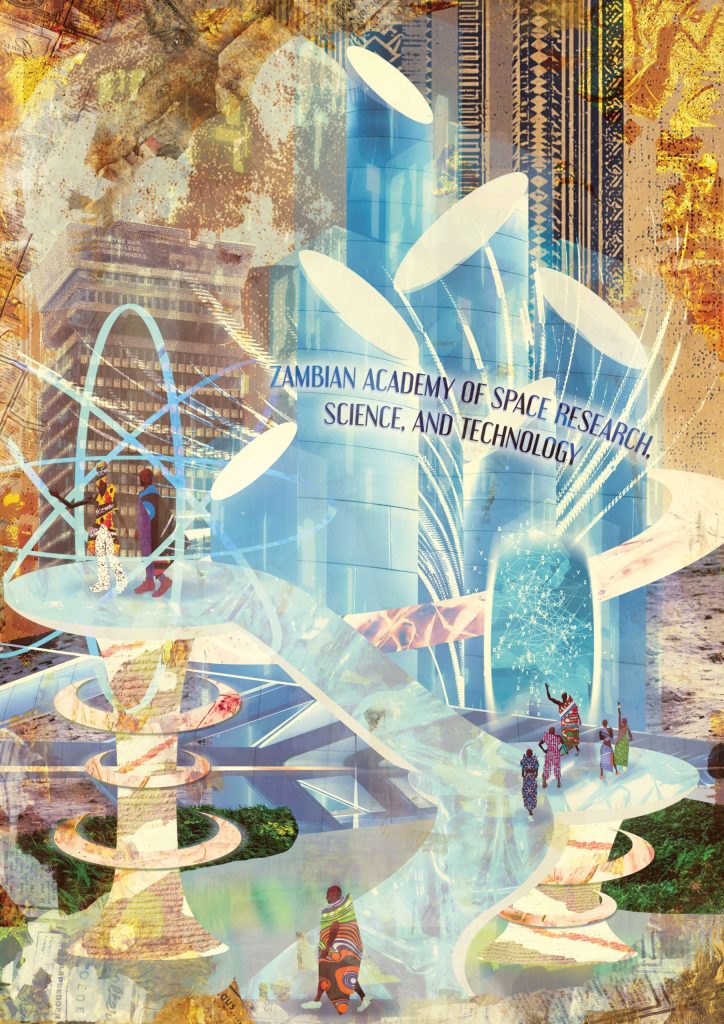

While the USA and USSR were engaged in a race to launch the first human into space, in a remote corner of the British colony of Northern Rhodesia, a different dream was taking shape. In 1960, Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso—a freedom fighter, science teacher, and radical thinker—established the Zambia National Academy of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy (ZNASSRP). His mission was bold: to send a human and two cats to the moon.

While Nkoloso’s space programme may have been inspired by the two superpowers, his ambitions and timeline far exceeded those of his counterparts. He didn’t just aim to place humans and animals on the moon—he envisioned reaching Mars.

Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso (1919–1989) was a former World War II soldier who served in the British Signal Corps. He was a freedom fighter contributing to Zambia’s liberation movement by making explosives to destabilise the colonial regime. He later became a science teacher, and also earned a law degree from the University of Zambia. He served as President Kaunda’s special representative to the African Liberation Centre, the headquarters for all the regional freedom movements fighting for independence.

His academy’s motto, “Where fate and human glory lead, we are always there,” reflected a belief in the boundless potential of African minds. Afronauts were rolled downhill in oil drums to simulate weightlessness. Though crude in appearance compared to the ‘gimbal rig’ developed by NASA in the late 1950s, it was innovative in its intent. He wanted his team to think differently, dream freely, and reject the notion of inferiority.

In an interview, Nkoloso’s son, Edward Mukuka Nkoloso Jr., recounts how, immediately after rolling and tumbling, and in a state of disorientation, Nkoloso Sr. would test them with questions to assess and develop their mental resilience.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the wave of independence was sweeping across Africa, and Zambia’s turn was inevitable. Nkoloso’s academy was a tool for self-realisation and complete decolonisation.

“To most Zambians, these people are just a bunch of crackpots, and from what I have seen, I am inclined to agree”.

– TIME Magazine Reporter, 1964.

Nkoloso was both an attentive student of history and a futurist, radical, and divergent thinker. He began his career teaching physics at a European school. Disillusioned by the limitations of the British education system, which he believed were inadequate in advancing Zambia’s interests after independence, he founded his school to teach science, mathematics, and religious education—a move seen by colonial administrators as subversive.

Nkoloso’s dream of space travel went beyond touching the stars; it was about mental liberation. He believed that colonial education turned Africans into servants of the colonial enterprise, rather than inventors. It trained them to extract rather than add value and innovate. It rewarded mimicry over mastery. This critique remains relevant: decades after independence, many African economies still rely heavily on extractive industries of finite minerals, exporting raw materials rather than producing finished goods.

Nkoloso also advocated the legitimisation of traditional African medicine, often dismissed as the work of “witch doctors”. He argued that Christian missionaries had discredited these practices and that they should coexist with Western medicine. Long before Western physicians acknowledged the value of traditional knowledge, Nkoloso viewed traditional healers as scientists and spiritual guides whose medical skills were deeply rooted in their respective habitats.

European commentators often noted the technical skill of African surgeons and the variety of roots and leaves herbalists used to treat multiple illnesses. Herbal medicine was also employed to prevent disease and promote health, especially during conception, pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. As historical anthropologists across the continent have observed, African healing practices involved more than just alleviating symptoms. They focused on understanding why an individual became ill. These pragmatic healing cultures often combined clinical and spiritual interventions and usually involved kin or peer groups managing and evaluating treatment options. This approach of viewing healing as a process involving both spiritual and collective elements shaped many societies’ public cultures of political engagement. Rituals aimed at healing the land or the state were seen as vital to collective prosperity, social cohesion, and addressing interpersonal tensions caused by disruptive forces like the slave trade or long-distance commerce. - Health in African History by Shane Doyle, Professor of African History at the University of Leeds.

The New York Mail

October 28, 1964

ZAMBIAN AFRONAUT MATHA MWAMBA LANDS ON MOON – A FIRST FOR HUMANITY

“Teacher! Don’t teach me nonsense”.

– Fela Anikulapo Kuti, 1986.

Challenging the prevailing assumptions of being mistaken for mad, confused, or a lunatic, Nkoloso would say to his son when asked why they were doing what they were doing, “…these Americans are not the greatest… if a bird can fly, why can’t you?” We don’t have wings, they would answer, or we are humans. Then he would tell them, ‘You have brains.’ – Kabinda Lemba, Faces of Africa Documentary – Mukuka Nkoloso: The Afronaut.

Edward Mukuka Nkoloso’s Zambian National Academy of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy served as a blueprint for decolonisation, self-belief, and self-determination. He knew too well the limitations of colonial structures if they were not addressed post-independence. Pan-African activist Joshua Maponga of Zimbabwe articulates Nkoloso’s sentiments in his paper on neocolonialism and strategies for decolonisation, titled On How to Decolonise Africa’s Systems — Education, Business, Health & More. He describes colonialism as a “brutal, dark chapter in our history. It was more than land occupation; it was a systematic takeover of our lives. It aimed to control the African mind. Our languages were suppressed, our stories silenced, our cultures were deemed inferior, our traditions mocked and marginalised. This was the essence of mental colonisation—a deep-rooted psychological warfare…Many African languages are endangered. This loss of language is a loss of identity. Our traditional education systems were dismantled and replaced with Western models. This disrupted the transmission of indigenous knowledge and created a disconnect from our past.”

Mutende News

October 25, 1964

FIRST WOMAN ON MOON IS ZAMBIAN. US AND USSR IN SHOCK

“..if a bird can fly, why can’t you?” We don’t have wings, they would answer.“You have brains.”

– Edward Mukuka Nkoloso, Founder, Zambian National Academy of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy

What if landing on the Moon or Mars wasn’t just about space travel, but about ascending to a higher state of consciousness? About mental decolonisation and liberation? What would Zambia have looked like 61 years later? Had Nkoloso’s vision succeeded—particularly through indigenous knowledge systems—it would have marked the dawn of an entirely different Zambia.

The foundations of education would have been redrawn. Indigenous languages would no longer have been viewed as obstacles to modernity, but as pathways to new scientific expressions. Zambia’s own Chokwe cosmology, like the Dogon of Mali, would have informed a homegrown astronomy—a sky mapped in native thought, as Nkoloso’s likely intended when he founded his school as an instrument of resistance to the limitations of the colonial education system.

The triumph of Matha Mwamba would have symbolised more than technical success. Her presence in space would have shattered embedded gender assumptions. Picture the image of a Bemba woman planting the Zambian flag in lunar dust. This would have ignited a generation of girls to dream in the language of physics, not in the confines of stereotypes.

Had Nkoloso’s afronauts made it to the moon, the event would have triggered the opposite of a subservient Africa. Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya might have followed suit with joint research programmes. The OAU (now the African Union) could have launched a pan-African Space Agency by the 1970s.

The geopolitical balance would shift, not just in allegiances, but in how the world conceptualised knowledge and power. Zambia and Africa as a whole would no longer be relegated to the margins of technological development, but centred as a source of innovation and curiosity, and a multipolar world would have become the norm—my perpetual dream.

In his book, Afrika Twasebana, Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe’s words of self-reliance urge readers to resist the reinvention of Africans in the likeness of imperial images. This stance of ownership and identity would form the basis for a new national identity. This dream had the capacity for a domino effect on multiple levels of integration. It was a vision that would translate today as “anything is possible.”

In global universities, curricula would diversify. Chokwe, Yoruba, and Ndebele cosmologies would stand alongside Copernicus and Kepler. Scholars from around the globe would come to study physics in Zambia. African fabrics and writing systems would adorn the walls of science departments, not as tokens, but as frameworks of theory. The revival of herbal sciences under a national health strategy guided by ancestral knowledge would emerge.

To call Nkoloso a madman is to misunderstand the language of liberation. A true artist is a liberated soul; he is never bound by rules that cage his imagination. His ambitions are a symbol of what true liberation would look like. Today, Nkoloso remains deeply relevant to artists, philosophers, and futurists alike.

His space programme has become a foundation for the Afrofuturist movement, inspiring works by a generation of Zambian creatives and intellectuals from across Africa and the world, including Aaron Samuel Mulenga, Anawana Haloba, Chembo Liandisha, Stary Mwaba and Cristina De Middel, among numerous others.

In 2023, the Lusaka Contemporary Art Centre screened a film titled After the Dream. It encouraged viewers to think about Zambia’s unrealised ambitions after independence, not just for freedom, but for progress in science and technology. It reminded audiences that while dreaming is powerful, realising those dreams takes determination and long-term effort.

It is nearly impossible to capture the essence of the man through the depictions and rhetoric associated with the term “afronauts.” When he passed away in 1989, former President of Namibia, Sam Nujoma, stated, “Speaking for the liberation movements, let me thank the government for giving this befitting send-off to a man who distinguished himself as a great freedom fighter. Oh, I wish he could remain alive and see the independence of Namibia, which is inevitable. I say to this great son of Africa that the struggle continues, and victory is certain.”

Nkoloso was a man whose influence transcended generations, whose sole mission was to secure a better future for the benefit of Zambians. His endeavours to pioneer man’s quest to space will continue to reverberate across time and space, a rocket ship propelled fiercely by the ambitions and dreams of contemporary Zambia.