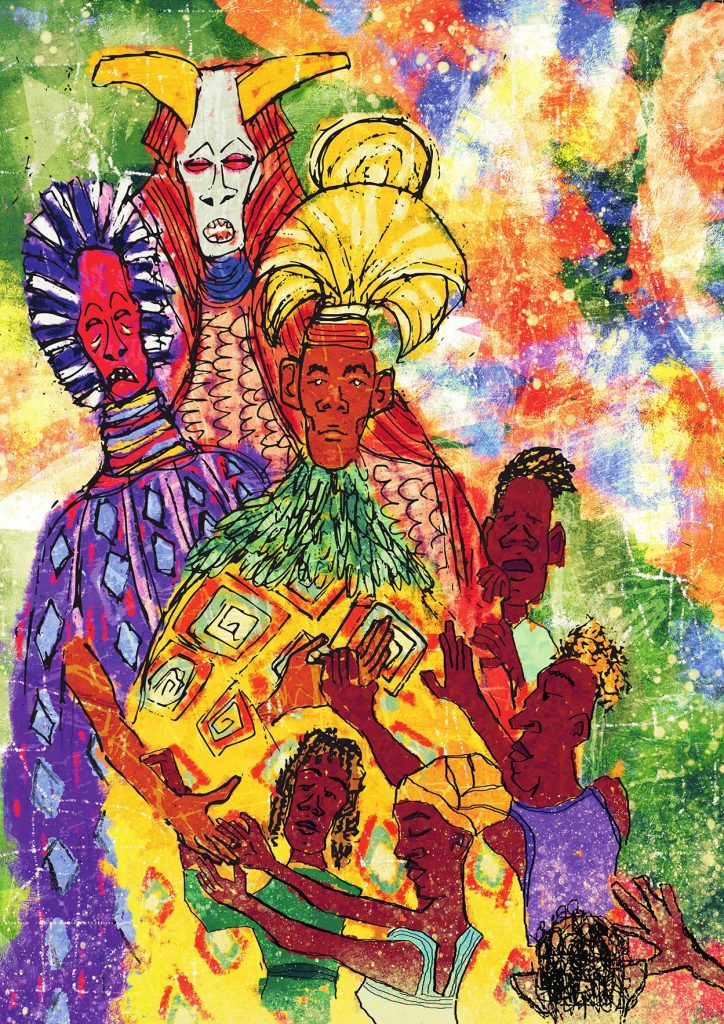

Healer or False Prophet?

The Ng’angas Hidden In Plain Sight

Driven by arrogance, I stepped over the hearth into Prophet Joseph’s world. My usual Saturdays were a slice of decadence before returning to the workweek, but there I was, visiting a Ng’anga. Determined to form an adventure, I convinced my friend Matilda to be my sidekick. We had no appointment, and our first realisation was that traditional healing practitioners have always worked from home. Outside, we were welcomed by a woman washing bright white cotton nappies and shaking ash from a brazier at the door. This suggested the presence of a newborn and meals eaten as a family. Prophet Joseph did not operate in a shrine; it was a clay-brick homestead in the heart of Lusaka, sitting on a large patch of land that chickens pecked and scratched.

Why Prophet Joseph? I wanted to speak to a traditional healer whose reputation preceded advertising. Through word of mouth, I was directed by a mall janitor who didn’t flinch when I asked. Zambians are friendly, but I was stunned by his charity and lack of judgement as he pointed me in the right direction—was my request not worth a raised eyebrow?

Amongst the bulletin boards and plastered walls of Zambian streets, between the commercials for cool drinks and real estate, sit advertisements for traditional healers. In bold word art fonts, they broadcast the ailments they can help you with, from help with illness to court cases to marital issues.

– Musonda Mukuka

All my spiritual searching has unfolded in Zambia, our Christian nation. As a family, we were dedicated to the United Church of Zambia, but there was a Qur’an in our home, and we never placed any book on top of it. That quiet reverence for all paths to the divine was woven into my upbringing. Spirituality was not communal but a private calling and a solo responsibility. I go to church by myself, drifting between congregations that fit the shape of my fellowship needs. This is why I recognise a contradiction within myself: the need for a witness, an anchor, a source of gravity to hold me to the truth. I have never needed company to visit a pastor. But for the Ng’anga, I did.

When we walked in, all my expectations were tossed out of the one small window in the dim room. It was a two-roomed structure with no floor, well partitioned and organised to meet the functions of family: a space to store kitchen items, an entertainment area with a television and a battery (because load-shedding was not spiritual), and the clues of a bedroom area shielded away with a curtain that cut the room in two. A baby slept in the cool corner of the room.

A man sat in the middle with his back turned. I cowered and wondered if this was part of the ritual—a mystical performance where he would recite my name, place of birth, and what I had eaten for breakfast. Would he divine that I never have breakfast? I fixated on his back, barely regarding the other man in the room: a fair man, clean-shaven and groomed, with his gaze fixed on a spot on the ground. He could have been the Ng’anga’s apprentice or another ‘believer’ searching for answers.

The Zambia Census Report 2022 does not provide specific data on the exact number of people working as traditional healers. However, it’s estimated that there are more than 35,000 traditional healers in Zambia. While a detailed census breakdown isn’t available, the 2022 data indicate that about 70% of the population uses traditional medicine.

A traditional healer in Zambia is called a Ng’anga. The term is neutral and simply translates as ‘healer’, but its meaning has evolved. Healer-diviners are believed to be called to their vocation by spirits. Because healing serves humanity, there is an intersection with Christianity, where healing is received through the Holy Spirit. This is explored in the paper titled Ng’angas – Zambian Healers-Diviners and Their Relationship with Pentecostal Christianity.

Today, traditional healing sits at the crossroads of culture, public health, politics, and religion. The government recognises healers and herbalists. The Traditional Health Practitioners Association of Zambia (THPAZ) encourages healers to register and pay a bi-annual fee of K146.41. The association certifies five categories of traditional health practitioners: Herbalists, Diviners, Healers, Spiritualists, and Traditional Birth Attendants.

It’s in our nature to never stop seeking answers. When modern medicine is inaccessible or unsatisfactory, people turn to nature. A burn is soothed at home with aloe; guava leaves and salt settle the stomach; migraines, infertility, and even cancer are sometimes treated with traditional medicine. While oaths, science, and procedure guide modern medicine, traditional African medicine is holistic, accounting for the mental, emotional, and cultural aspects of health.

This line of thought led me to Musonda Kapena, co-founder of the Namfumu Conservation Trust and an expert in ethnobotany. I asked her what led us back to nature and what distinguishes a witch doctor from a Ng’anga or herbalist.

“Every human civilisation has an herbal healing system—all medicine started in the forest. Through tangible and intangible means, humans have used spiritual, intuitive, and learned processes to heal,” Musonda shared. She emphasised that though all traditional health practitioners relied on nature to heal, their intentions and approach set them apart. She reminded me that the Witchcraft Act of 1930 criminalises the practice or accusation of witchcraft in Zambia.

Her practice at Namfumu incorporates deep empathy, botany, and indigenous knowledge to develop scientifically dosed herbal therapies that address a myriad of ailments. She engages sustainably with nature and encourages all humans to adopt a responsible lifestyle that does not contribute to disease.

Healers advertising on roadside banners usually treat mainstream ailments, such as malaria, but highlight flashy services, including bringing back lost lovers, enlarging manhood, magic wallets, and lucky charms for court cases and exams. These sorts of practices defy nature and the principle of free will. But because there’s no scientific proof required, the wilder the claim, the more attention it attracts.

Prophet Joseph, by contrast, did not believe in advertising.

As I sat there, I expected him to ask why I’d come, like a doctor would. My friend suggested I pose a hypothetical issue, but I couldn’t suppress my superstition. My lips were dry, and my palms were moist as I waited for the spell of silence to be broken. When the moment came, the neat man by the window spoke. My mistake dawned on me.

“Ndine Prophet Joseph. Tingamitandizeni…”

(Translation: We can help you…)

The subversion was shocking. This was the prophet? He was cordial, trim, and almost professional. He introduced his apprentice, who had once been a patient, and nodded before turning back to his phone. Prophet Joseph looked me in the eye, nodded, and continued talking until we found a common language: Nyanja. I noticed an accent, though I couldn’t place it. The baby lay asleep as we talked.

He said he didn’t choose this life—he was born this way, born with the ability to see visions. At church, he saw disturbing flashes about elders. In public, he foresaw misfortunes. His parents told him to be quiet, blend in, and never share what he saw. Over time, he came to understand the purpose behind his visions—to support and assist in God’s work. However, the hypocrisy he found in the church sent him away.

He met his wife during his prodigal years. They married in 2018 and now have four children. He eventually found a church that brought him peace. I guessed he was in his early to mid-thirties, but I didn’t ask—afraid it might derail our conversation.

“Sini gwila mankwala…” he said, opening his palms to show they were clean. Aside from a cane leaning against the wall, no herbs or strange objects were in sight. He explained that he was not a witch doctor or herbalist but a healer, and all his power came from God.

(Translation: I do not use witchcraft…)

When asked if he healed for money, he deflected. He spoke about false prophets and scammer pastors who sought spiritual powers through dark means to grow their churches. He hinted at a hierarchy—more followers meant more money. The irony struck me: influencers also operate on the principle of attention and influence. Are they also scammers?

Many people visit Prophet Joseph, and he dedicates himself to prayer to see the problem, the source, and how to eradicate it permanently. His manner was evangelical, reminding me to stay on the path with the Christian God, who didn’t ask for anything to heal us because Jesus Christ paid the price. He shared his extensive beliefs in evil and how people attract it through desperation, greed, desire, and careless exposure.

His vigilance against evil is shared by mobs who harm elderly people accused of witchcraft. The accused are often alone, exhibiting cognitive decline and vulnerability. Such accusations are fatal, resulting in the violent loss of life outside of the justice system. I shudder to think of what I would do if my own mother were found in such a situation.

I had more questions than answers.

He was as curious about me as I was about him. He asked again why I was there.

To most, writing is not a real profession. We sat across from each other, playing tennis with our whys. Ultimately, I concluded that there was no definitive answer.

Traditional healing was as integral to African culture as storytelling. At one point in time, traditional healers existed freely, much like storytellers around a fire. The forms of the practice have changed. I write on a laptop, and people like Prophet Joseph work with what they have. When asked where the words I write come from, I would have the same answer as he: pictures in my mind.

Since Zambia was declared a Christian nation, consulting ng’angas has increasingly become a taboo. Many see their practices as conflicting with both the nation’s Christian values and its identity.

– Musonda Mukuka

Eventually, he stopped asking. The baby stirred awake. His wife came in, nursed him, and then handed him to the apprentice. She listened as we spoke. When I’d said my goodbyes, Prophet Joseph warned me: “Be careful. There is good and bad everywhere.”

I was tempted to ask about my weight, fertility, or future romantic prospects, but it all felt trivial. He spoke of people who were carried in on reed mats and walked away healed. I knew I wouldn’t get the answers I needed for closure. Heeding his warning, I lost the courage or curiosity to visit more traditional healers.

I reached into my bag for a note I felt was worth his time and hid it in my palm before I knelt.

“Ah, siba ona,” his wife said, the baby now on her hip.

(Translation: He can’t see.)

What? I looked up at him, scanning his face. For the first time, I saw the glassy mist in his eyes.

His wife quickly filled in the gaps. It was clear this was her role—explaining her husband’s imperceptible blindness. After a bout of headaches, Prophet Joseph suddenly went blind seven months prior. The hospital prescribed Vitamin B as the headaches worsened. His work worsens his condition, his visions drain him, and his prayer is a strenuous effort. I asked if he was afraid—and why God hadn’t healed him. He answered that it is “all to the glory of God.”

I thought of the many who advertised potions for wealth but were not rich themselves. I slipped the money directly into his palm, and he thanked me, saying he would see me again.

Did he see it—or was that just something people said?