30 Years of Afrofuturism: Zambia’s Continued Contribution to the Field of Afrofuturism

To know where we are going, we must know where we have come from. This is a concept well described through the term Sankofa, which is a Ghanaian Twi word meaning “to retrieve” or “to go back and get.” When contemplating the future, it would be easy to neglect the past but to forge a brighter future, we must retrace our steps and learn from our past.

A question I believe Afrofuturism aims to answer is, “In what ways can a different, more affirmative future be envisioned for black individuals?” At a micro level, this question could be addressed by the people of Zambia. Over the decades, Zambian visual artists, writers, and thinkers have made significant contributions to the field of Afrofuturism through their creative endeavours. It is within their collective work that we discover facets of the response to the question of what this reimagined future would look like.

To begin with, one must consider the origin of the term Afrofuturism. It was coined by American cultural critic Mark Dery in 1994 while commenting on the intersection of science fiction and the African-American experience. Dery states, “Speculative fiction treating African-American themes and concerns and appropriating images of technology can be called Afrofuturism.” Similarly, writer Ytasha Womack defines Afrofuturism as an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation. It is stated that Afrofuturists sought to unearth the obscured histories of people of African descent and their roles in the realms of science, technology, and science fiction.

Though the term Afrofuturism was coined in the West, we must acknowledge that the concept of envisioning the future has always been present in Africa. A significant moment in time, when African people embraced futuristic ideals was during white settler colonialism. As many African nations grappled for independence, they would have engaged with imaginings of what a future of liberation could look like, and Zambia was no exception in this regard.

Namwali Serpell, one of Zambia’s prolific writers, explores the concept of Afrofuturism in her science fiction novel The Old Drift. Serpell makes a lasting imprint on science fiction literature by drawing from Zambia (her country of origin) to craft an impactful narrative engaging with concepts of revolution and ideas of a promising future. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Serpell discloses her intent to “create a sense of a homegrown revolution that could happen in Zambia. Not just a technological revolution, but a political revolution that would be about Zambia — and not about other places coming in to save us.” Part of Serpell’s revolution is connected to Mukuka Nkoloso, who was once a grade-school science teacher and the director of Zambia’s National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy. Nkoloso aspired to launch Zambians to Mars in hopes of beating the U.S.A. and Soviet Union during the space race of the 1960s.

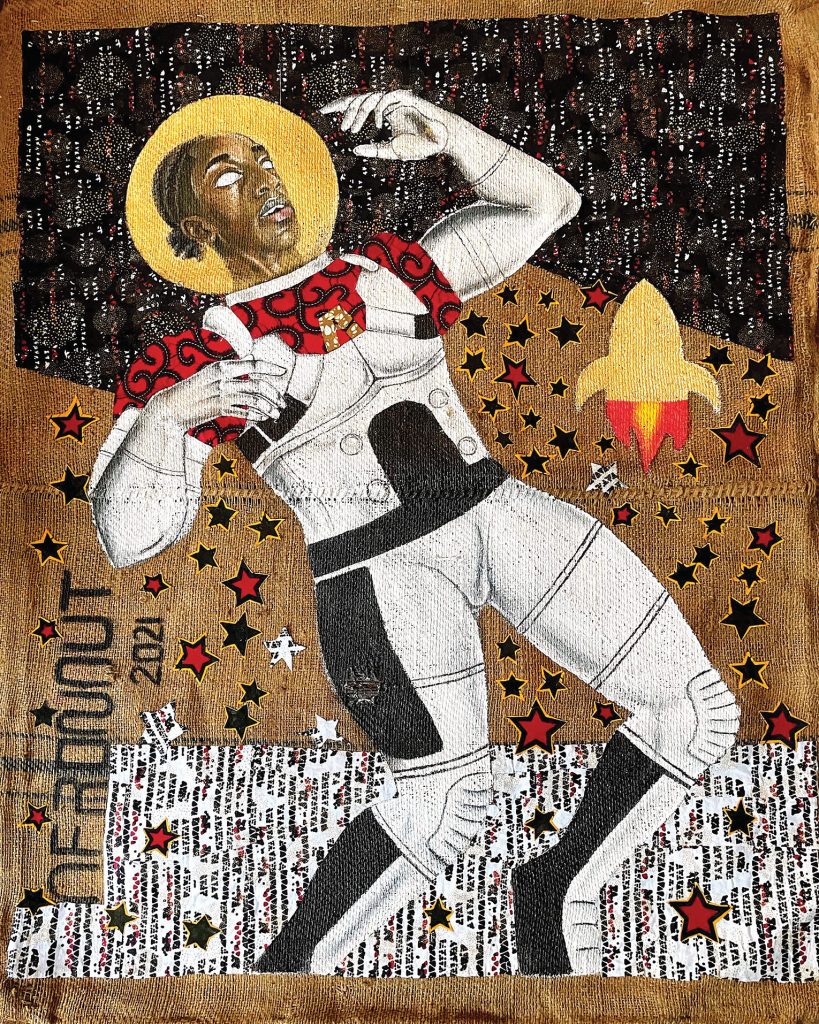

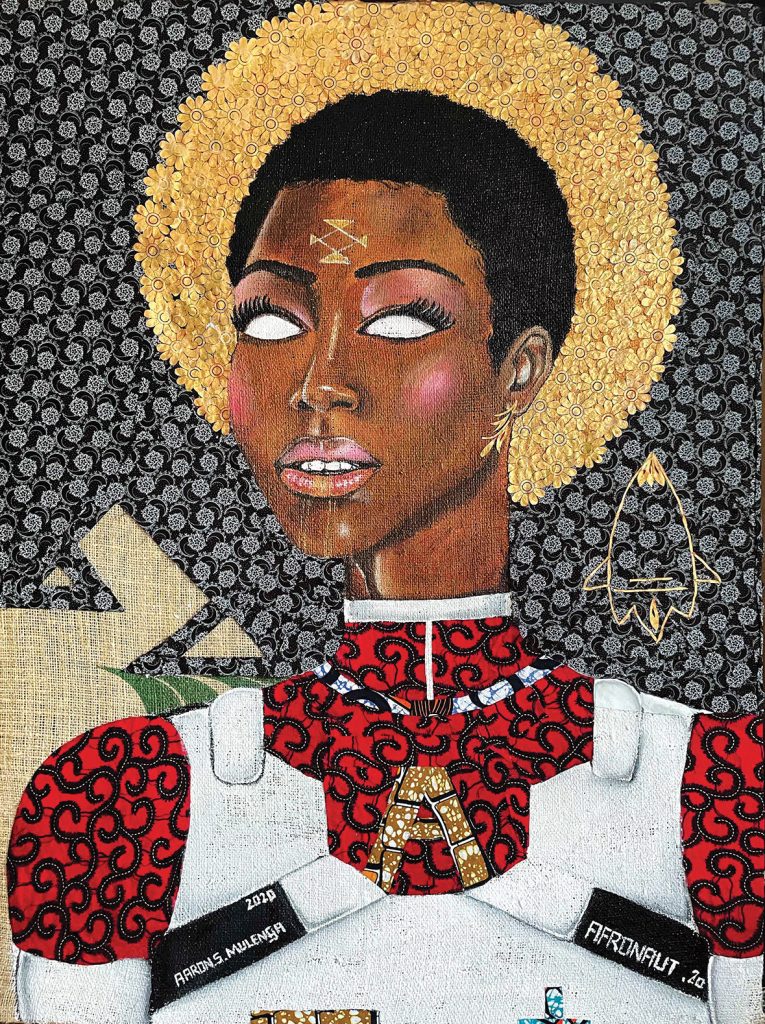

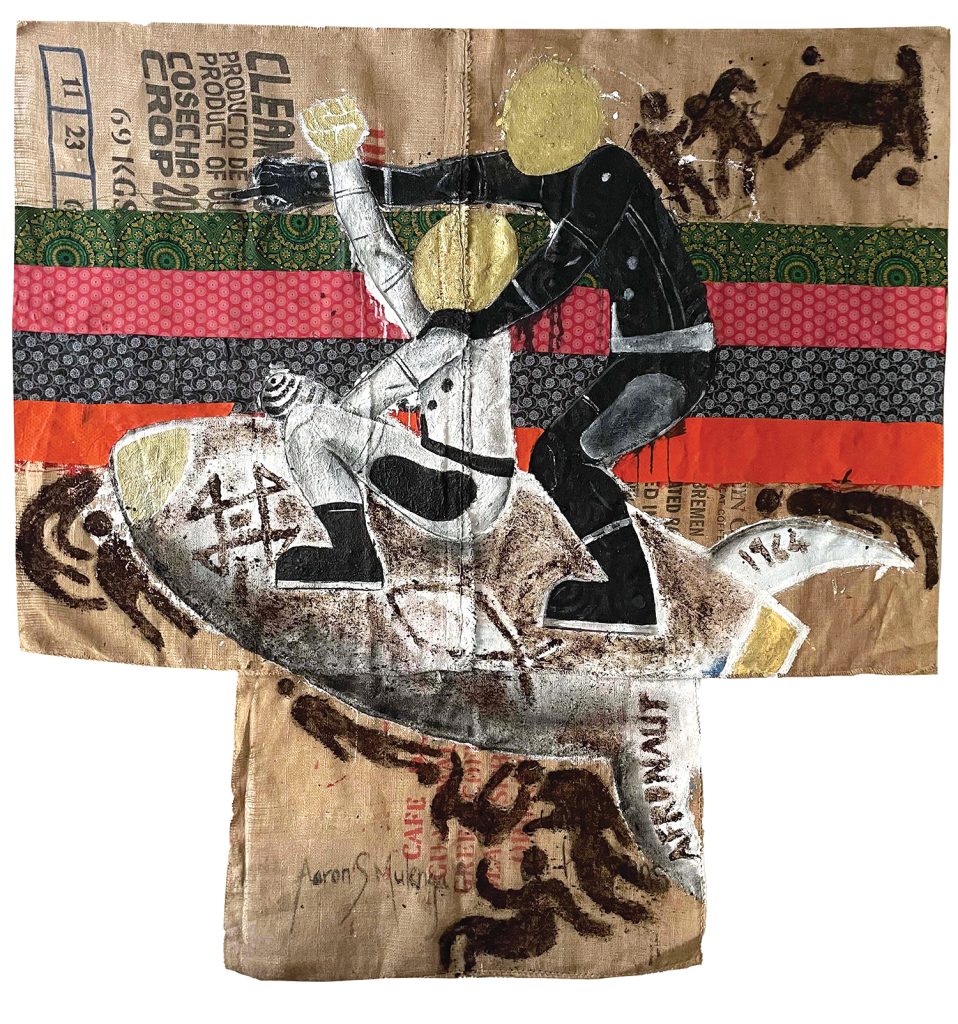

Although Zambia did not realise their goal of reaching the moon or launching a rocket into space, Nkoloso coined the term Afronauts, which could be construed as “African astronaut.” This term would be taken up by artists who found resonance with his ambitious plan to have Africans in space as early as the 1960s. One must consider the magnitude of such a dream while living under colonial subjugation. While his contemporaries had their feet on the ground, Nkoloso dared to hold his head in the stars. He was occupied with a different kind of liberation, daring to dream about emancipation transcending national boundaries. The Afronaut story and Nkoloso’s enduring legacy have indeed transcended borders, inspiring artists from Zambia, such as myself and Stary Mwaba, filmmaker Nuotomo Bodomo from Ghana, and Gerald Machona from Zimbabwe, to mention but a few from the inexhaustible list when considering how far the Afronauts have travelled by way of the arts. The tale of the Afronaut has an intrigue that reaches far beyond the confines of Zambia. It speaks to a collective vision that resonates with many: the prospects of hope and the possibilities and imaginings of an optimistic future for black individuals.

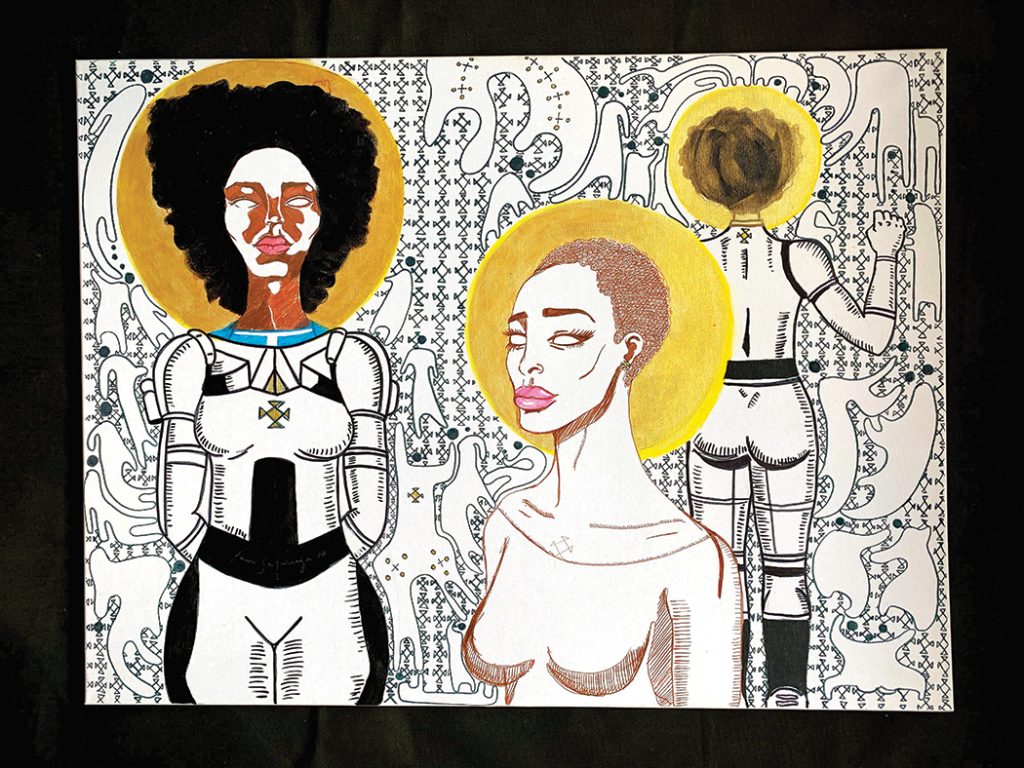

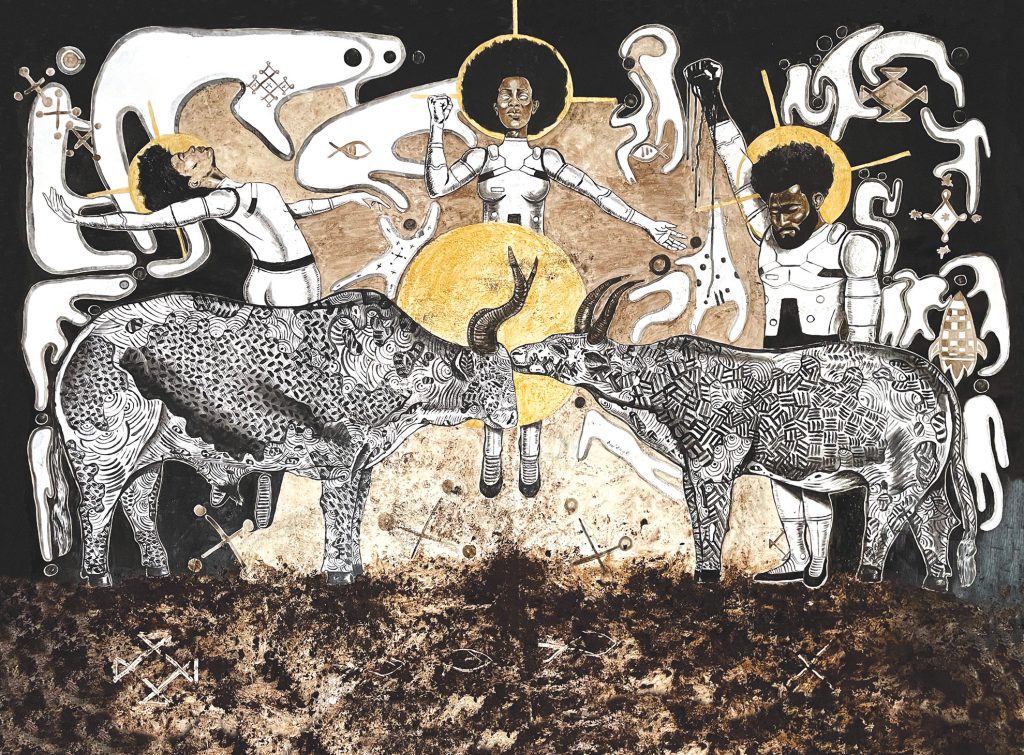

In my ongoing series, Afronauts, I place these figures in various scenarios. The materials I employ in my compositions give meaning to the pieces owing to the historical significance behind them. I draw from varied references when I create, some stemming from my personal experiences or addressing issues I consider pressing. The artwork entitled From the Ground Up! Ulubuto scrutinises the concepts of spirituality and space travel. The Afronauts series draws from Zambian cultural references and Christian iconography to imagine how different aspects of Zambian life can converge to consider a better future for the Zambian people. The Afronauts don golden helmets that evoke halos reminiscent of those adorning Christian saints. In the Ulubuto piece, three human figures appear behind the two cows, evoking a semblance of the Holy Trinity. The cows are a Zambian cultural reference, denoting wealth, while the amber and russet hues at the bottom of the piece presents a blend of coffee and acrylic paint. The markings in the coffee contain symbolism from the Chokwe and ba Kongo peoples. Through these artworks, I intend to engage with Zambia’s history while speculatively exploring ideas of the future. In so doing, I weave Zambia’s cultural heritage with its missionary past while curating triumphant moments from the nation’s past that point towards a brighter future for its people. This practice does not negate the stains of the past, such as colonisation or the tumultuous transition into self-governance; it instead gazes hopefully toward the future by learning from history.

Nnedi Okorafor is a Nigerian author interested in centring African thought in Afrofuturism. She employs a different tool to perform this task of re-centring “African futurism.” Okorafor interprets African futurism as being concerned with visions of the future and anchored in technology. It is centred on and is predominantly written by people of African descent, and it is rooted first and foremost in Africa. It is less concerned with ‘what could have been’ and more with ‘what is and will be’. African futurism acknowledges, grapples with, and carries “what has been.” Its default is non-western; its centre is African.

Okorafor’s contribution is essential because it expands the sphere of inclusion when considering who has access to concepts of the future and the imagination of its portrayal. Similarly, one may consider the Zambian contribution to the field of Afrofuturism through playwright/play director Mwenya B. Kabwe and her production Astronautus Afrikanus, which has been described as celebrating imagination, creative freedom, and indigenous African knowledge systems by drawing directly from the story of Mukuka Nkoloso. This play was staged in Makhanda, South Africa, at the Rhodes University Drama Department. According to Kabwe, the project’s genesis lies in the reclamation of Nkoloso as a utopian visionary and an African futurist who can see a Zambian lunar mission as a metaphor for an independent Northern Rhodesia.

In an interview with Michelle Johnson, Masiyaleti Mbewe, a Zambian futurist writer, photographer, and activist, speaks about her artistic practice and engagement with the concepts of Afrofuturism. Mbewe currently resides in Namibia, where she presented an exhibition, “The Afrofuturist Village,” which navigates an alternative future for Africans. Mbewe reveals that her objective was to frustrate the conventional ideas surrounding the visual impressions of Afrofuturism and tether them back to African spirituality and the concept of ubuntu. She advocates for removing linearity in futuristic contemplations, citing the influence of the past as a critical ingredient for this paradigm shift.

Through Mbewe’s expressions, we are inevitably drawn back to the concept of Sankofa, where the past influences and interacts with the future in a myriad of ways. It is imperative for artists and scholars interested in probing the discourse of the future to continue looking back at history and cultural narratives, back to marginalised figures such as Nkoloso and their hope for the improbable. In so doing, such absurd thoughts are capable of inspiring generations.

In Nkoloso’s evocation of Afrofuturism, which he may have referred to by a different name, he envisioned a future where Zambians could be pioneers in space — which was and still is a radical re-visioning of the world. In a way, the different Zambians undertaking this labour of carrying these narratives with them wherever they go play a part in conceptualising the bright future they hope to claim. I imagine them as the new Afronauts who are not traversing space but rather occupying new territories that enable viewers and readers to continue imagining what bright, purposeful futures could look like for Zambians and, by extension, themselves.